Jeff Howard explains what it means for a state to be a party to the ICCPR and how individuals can issue complaints about violations of free speech to the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

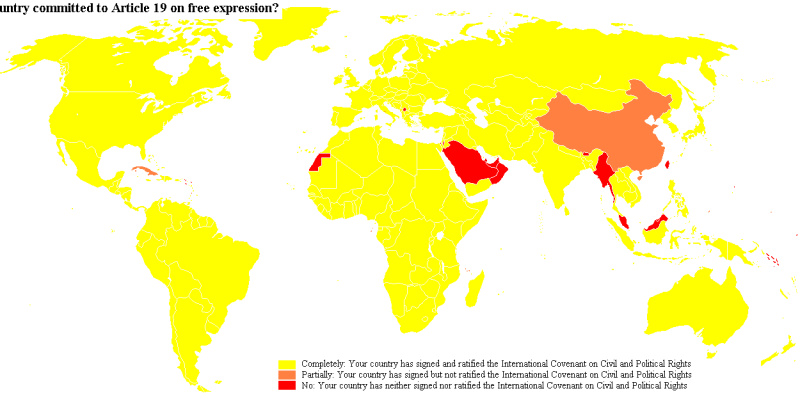

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is the multilateral treaty agreement central to anchoring freedom of expression in international human rights law. The vast majority of the world’s nations have both signed and ratified the treaty. Nations that have signed but not ratified include China, Comoros, Cuba, Nauru, Palau, Sao Tome and Principe, and Saint Lucia. Nations that have neither signed nor ratified include Saudi Arabia, Antigua and Barbuda, Bhutan, Brunei, Myanmar, Fiji, Kiribati, Malaysia, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Oman, Qatar, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Singapore, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, the United Arab Emirates and the Vatican.

But what does it mean to be a signatory or a ratifying party to the ICCPR? And if your country is a party to the ICCPR (see here to confirm), how might you personally use it to advance your individual right to free speech?

I. What it means to be a party to the ICCPR

When a state signs the ICCPR, it does not become legally bound by it, but rather declares its intentto become so bound, and it promises to refrain from actions that would defeat the “object and purpose” of the treaty until such a time. Ratification (or, if there is no prior signature, “accession”) is what establishes the legally binding status of a country’s commitment to the ICCPR. However, it is strikingly unclear what a commitment’s status as “legally binding” actually involves. Many suppose that a necessary condition of an agreement’s status as legally binding is that the content of the agreementis also coercively enforceable. In the case of the ICCPR, as so often in international law, that is false. There is no official mechanism for international enforcement of the ICCPR.

So what does “legally binding” mean? It means simply that a ratifying party is subject to a treaty obligation to ensure that its domestic political system protects the rights specified in the ICCPR, including measures (such as training and encouragement) outside of the formal law. No particular institutional mechanism is recommended as a means of such protection domestically; the UN’s Human Rights Committee (UNHRC), taskedwith interpreting and clarifying the ICCPR’s precise demands, contends that, “[A]ll branches of government (executive, legislative and judicial), and other public or governmental authorities, at whatever level – national, regional or local – are in a position to engage the responsibility of the State Party.” This language does not determine any exact method of protecting rights, but it insists on the judiciary’s involvement; state parties are bound to “develop the possibilities of judicial remedy”. As many jurists are reluctant to apply international human rights law in domestic decisions (despite treaty obligation to do so), some scholars have advocated that the best way for a country to become ICCPR-compliant is for its jurists to “discover” the treaty’s rights already embedded, implicitly, in their respective country’s legal traditions. One legal scholar notes that this is how Australia became compliant with the ICCPR’s provisions on freedom of speech, by identifying an implied right to communication presupposed by democratic processes.

Of course, even in cases where there is a domestic process of judicial review, everything hangs on the willingness of judges to take seriously the legal obligation to uphold the ICCPR (or the relevant domestic statutes that render the legal system typically compliant with it). So we come to the fundamental question: what international legal recourse is available to citizens of a ratifying or acceding state? If youare a citizen of a state and want to protest some violation, what can you do? It all depends on whether your country has, in addition to becoming a party of the ICCPR, signed the First Optional Protocolto the ICCPR.

II. The First Optional Protocol

The First Optional Protocol is a distinct treaty agreement that permits private citizens to issue complaints to the UNHRC that their country has contravened a provision of the ICCPR. 114 states have ratified or acceded to this protocol. 53 countries who have ratified or acceded to the ICCPR have not ratified or acceded to the Protocol. To see whether your country is a member, see here.

According to the First Optional Protocol, the UNHRC formally accepts complaints from citizens of countries who are parties to the Protocol, subsequently deciding whether the disputed statutes or state actions contravene, or rest in compliance with, the ICCPR. The legal ruling is authoritative but not enforceable.

Citizens of former Soviet states in particular have experienced considerable recent success in winning their cases with the UNHRC. In 2009, the committee ruled in Mavlonov and Sa’di v Uzbekistan that the Uzbek government violated the rights of Uzbek citizens when it refused to renew the registration of a newspaper that explored educational and occupational injustices faced by Tajik-language speakers. In 2011, the Human Rights committee ruled in Kungurov v Uzbekistanthat the Uzbek government violated Article 19 by refusing to register an NGO called “Democracy and Rights”. Another 2011 case, Toktakunov v Kyrgyzstan, ruled that citizens’ rights under Article 19 were violated when Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Justice refused to release statistics on the number of death sentences and penitentiary inmates. And in Zalesskaya v Belarus(2011), the committee ruled in favour a citizens who were fined heavily when they distributed two registered newspapers – Tovarishch (“Comrade”) and Narodnaya Volya (“People’s Will”) – without having received previous approval.

Eastern Europe by no means exhausts the UNHRC’s ambit. In Dissanakye v Sri Lanka(2008), a prominent member of the Sri Lankan parliament claimed that he would not accept any “shameful” decision by the country’s supreme court on the division of defence powers between the president and defence minister; he was subsequently charged with contempt of court and imprisoned for two years. The UNHRC claimed that such imprisonment violated his rights under Article 19. In Coleman v. Australia(2006), the UNHRC decided that a city council violated a citizen’s rights under Article 19 when it imprisoned and fined him for delivering a loud address on substantive political matters, such as mining and land rights, without a permit. And in Shin v. Republic of Korea(2004), the UNHRC ruled that a painter’s Article 19 rights were violated when he was arrested after painting a piece that depicted South Korea as an American puppet.

Appeals to the Human Rights Committee UNHRC are not always successful. It is important to stress that one must exhaust all available domestic remedies in order to be able to complain to the committee, or it will refuse to hear the case. Many cases are never reviewed by the UNHRC if, say, there is a further court in one’s country to which one could appeal one’s case. In these situations, the UNHRC will release no opinion on the case whatsoever. The most famous recent such incident was Said Ahmad and Abdol-Hamid v Denmarkin 2008 – the case at the heart of the Danish cartoon crisis. Because a domestic appeal was still underway as to whether a newspaper that published incendiary cartoons of Muhammed could be held criminally liable for such a publication, the Human Rights Committee refused to hear the case.

The UNHRC also routinely refuses to hear cases, thereby deferring to domestic authorities, when it contends that some evidence is unsubstantiated. In the 2008 case Sama Gbondo v Germany, a nationalised German of Sierra Leonan birth was convicted of libel after he referred to a police officer as a racist when the officer, investigating violations of transport regulations, used a racial slur. The offender claimed his rights of free expression were violated by the conviction; the UNHRC contended there the claims were “insufficiently substantiated” to evaluate the matter in question. In such cases, the effect is to decline to comment, leaving the domestic ruling to stand.

And then, of course, there are cases in which the HRC hears the case but resolves that no contraventions of the ICCPR have transpired. In Hertzberg et al. v Finland(1985), the UNHRC decided that a Finnish broadcaster acted consistently with Article 19 when he censored two television programs addressing homosexuality, on the grounds that “a certain margin of discretion must be accorded to the responsible national authorities.” In De Jorge Asensi v Spain, a 2008 case in which an army colonel complained that proper selection protocols were not followed in awarding promotions, the UNHRC ruled that none of his ICCPR-protected rights – including his Article 19 rights to seek and receive information – were violated by the secret nature of the decision. In Nam v. Korea (2003), the UNHRC ruled that a law prohibiting the non-governmental publication of Korean language textbooks did not violate authors’ rights to express their professional knowledge freely. And in Robert Faurisson v. France(1996), which concerned an academic who disputed the existence of gas chambers at Auschwitz, the committee ruled that France’s Gaysott Act, which makes it a crime to contest the findings of the Nuremberg Trials, does not violate Article 19.

If the UNHRC rules that a contravention of the ICCPR has transpired, it will “urge” the party country to revisit the case, sometimes also recommending the legal removal of the relevant ICCPR-violating law and, depending on the kind of case, the awarding of compensatory and punitive damages to those whose rights have been violated. Sometimes an UNHRC ruling will motivate internal change; sometimes not.The UNHRC requests reports from member states on how they have sought to implement the relevant changes, but in many cases they do not receive them.

III. Resistance to the First Optional Protocol: the US case

Countries that are parties to the ICCPR but have nevertheless refused to sign the First Optional Protocol lack any formal complaint mechanism to the UNHRC. The US voted to support the creation of the First Optional Protocol, and yet it has refused to ratify it. Human rights groups have long criticised the US for this refusal, which – when combined with the massive list of US reservations to the ICCPR – effectively neuters the ICCPR’s impact on American domestic legal practice. Scholarly debates over why the US has taken an apparently paradoxical stance on international human rights law, advocating fervently for its expansion while simultaneously refusing to be bound by it, suggest a range of possible reasons. Some of the most popular explanations include the role played by “American exceptionalism” as a salient idea within US political and legal discourse: the idea that the US is unique among nations in the moral quality of its institutions, and therefore that international human rights law exists to protect those who lack the good fortune to be protected already by the US constitution. More cynically, scholars cite the general suspicion with, and possible arrogance toward, foreign people and cultures that persists not merely among the American populace, but among the elite. Conservatives continue to scoff at the thought of invoking foreign law in domestic legal opinions. One historian referred to the issue as the product of “an ethnocentric world view, a perspective suspicious or disdainful of things foreign” that has prevailed in the postwar era.

Another scholar resists the exceptionalist explanation of American resistance to human rights conventions; we can fruitfully apply his analysis to consideration of the First Optional Protocol. He cites four factors that the US and that together account for American resistance. The first is the US’s significant geopolitical power, which gives it an advantage in bargaining agreements. Realist international relations theory tells us that when a power can strike agreements that suit its own instrumentally rational interests beyond the point that would be fair, it will do so. However, because human rights conventions are not enforced through a mechanism of bargaining, but rather judicially, signing the First Optional Protocol would irrationally forfeit the US’s ability to press its interests. This account is consistent with American resistance to the international criminal court, possibly owing partially to concerns about its own soldiers’ criminal liability. Secondly, the US possesses deeply stable democratic institutions. While the moderate leaderships of burgeoning democracies may seek to protect their fragile institutions from internal threats from the extreme right and left by securing international protections, stable democracies like the US have little to gain. Thirdly, beyond the fact that US derives no clear benefit from signing the First Optional Protocol, many on the American right, while affirming the general idea of universal human rights standards, dispute the way those standards are specified and interpreted by international organisations. If southerners dislike elites with whom they disagree in Washington DC meddling in their affairs, it is unsurprising they are even more opposed to foreigners doing so. Finally, the US political system is highly decentralised; the more decentralised a system, the more veto opportunities, and the less likely it is that international obligations will be accepted. These features of the American case can, of course, be generalised: regional dominance, democratic stability, ideological conservatism, and decentralisation all push against acceptance of international conventions, especially binding ones. This analysis applies not merely to the First Optional Protocol, but to the ICCPR itself. Saudi Arabia, which we examine in the final section, is both regionally dominant and ideologically conservative and has neither signed nor ratified the ICCPR.

IV. Resistance to the ICCPR: the Chinese case (signature without ratification)

After signing the ICCPR in 1977, the US government finally ratified it in 1992. That long delay between signature and ratification may have contributed to a trend: while China signed the ICCPR in 1998, it has not yet ratified it. The Chinese government has issued several official documents expressing its intention to ratify the ICCPR, although no specific timeline has been provided. As one document explains, “China has signed the ‘International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)’ and will continue legislative, judicial and administrative reforms to make domestic laws better linked with this treaty, and prepare the ground for approval of the ICCPR.”

However, there has been no official explanation as to what exact conflicts between the Covenant ICCPR and Chinese domestic law stand in need of reconciliation. According to official legal scholars, it has little to do with Article 19’s protections on freedom of speech, as freedom of speech is already “protected” in Article 35 of the Chinese constitution.The two most pressing issues that appear in legal discussions are capital punishment and re-education through labour, as the Chinese penal code classifies dozens of highly nebulous crimes (such as endangering public security or public order) as capital offences. China’s system of “re-education through labour” detains people of minor crimes such as petty theft or prostitution for up to three years in labour camps. The sentences are issued by the police, not the judicial system, thereby contravening Article 9.4 of the ICCPR. Other problems for reconciliation include Article 12’s guarantee of freedom of movement, which appears to conflict with the hukou, China’s residential permit system. And Article 22.1’s protections on freedom of association, which includes the right to form and join trade union, rests in conflict with Chinese law’s prohibition on the independent creation of unions outside of the All-China Trade Union system.

One of the foremost arguments used to explain the slow pace of reconciliation with ICCPR in China concerns the claim that economic development is a necessary precursor to affording full human rights protections. The claim is that strict management of China’s era of development, which will equip all Chinese with the conditions for material success and prosperity, would be undermined be premature adoption of a human rights regime. As one Chinese state councilor said in 2005, “Poverty is the main barrier to the progress of human rights in the region. Thus we have no choice but to consider development—improving economic, social and cultural conditions—as our most important task.” But this rhetoric implies that there should be a slow relaxation of opposition to human rights, as development proceeds; yet this is the opposite of what is transpiring. Chinese officials’ words must be taken with a grain of salt; the New York Timesreported recently that Chinese officials are supporting “some of the tightest limits on media and internet freedoms in years”.

V. Resistance to the ICCPR: reservations and declarations

If China someday signs and ratifies the ICCPR, it would almost certainly follow the example of numerous current parties and adopt explicit reservations: conditions that states place on their commitment to the treaty. While the reservations cannot be incompatible with the “object and purpose” of the treaty, they reflect the most naked instances of governments’ official objections to the ICCPR on ideological and self-interested grounds that are open to public knowledge. Some scholars and activists cast the reservation process as one which allows for moral disagreement, and interpretive and institutional variability, without fundamentally imperilling the core aims of the treaty; others cast it as a way for illiberal countries to eviscerate human rights while claiming to be ICCPR-compliant.

Bahrain is a key example: it interprets provisions against gender discrimination (Article 3), freedom of religion (Article 18), and the rights of the family (Article 21) as “not affecting in any way the prescriptions of the Islamic sharia” (Note that Bahrain is nota party to the First Optional Protocol; its citizens have to no official avenues for complaint.) There is, of course, an argument that even such minimal participation in the international human rights community begins the slow process of evolution toward full recognition of human rights.Pakistan is another country that has issued reservations interpreting various articles of the ICCPR to be consistent with its own partly sharia-law inspired constitution. Critics nevertheless contend that such reservations undermine, rather than advance, the cause of freedom in these countries.

On matters relating to Article 19, one of the most recurrently cited reservations concerns countries’ desire to retain the right to require licenses for all broadcasting; Luxembourg, Monaco, Ireland, and Italy all include such reservations. One of Malta’s reservations interprets Article 19 to be consistent with the requirement that “public officers” not be permitted to engage in active political discussion during hours of work. More ominously, Malta also interprets Article 19 to be consistent with a domestic law whose purpose is to “regulate the limitations on the political activities of aliens”.

VI. Resistance to the ICCPR: the case of Saudi Arabia (neither signature nor ratification)

Saudi Arabia has neither signed, nor ratified or acceded to, the ICCPR. Because there is not a transparent political debate in Saudi Arabia about foreign policy, it is difficult to identify its precise reasons for choosing not to sign or ratify the ICCPR. As we have seen, its reluctance cannot be explained by a fear of coercive enforcement; even under the First Optional Protocol, there are no enforcement mechanisms whatsoever. Indeed, Saudi Arabia has ratified the Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, despite its persisting illiberal reputation on issues of gender equality. Why does it not then sign the ICCPR?

Let us imagine how a principled argument from Saudi Arabia might go. This potential explanation hinges on the view that the ICCPR is not actually an international agreement; it does not actually seek to specify the moral common ground of all the societies on the planet. Rather, it is a distinctively westernagreement, articulating a view of human rights that is alien to the moral sensibilities and commitments of Saudi Arabia’s people. Therefore, according to his argument, the ICCPR is best viewed as an artifice of the west, incapable of accounting for the deep convictions of those who disagree fundamentally who the western interpretation of what it means to treat an individual with dignity. The Middle East needs something different – and it hassomething: the Arab Charter on Human Rights of 2004, a Saudi-led effort to, as one scholar put it, “create a new formula to address the historic and fundamental question of whether Islamic principles can be compatible with the universality of human rights”. The charter answers “yes” to this question, but by articulating a thinner vision of rights than that announced in the ICCPR.

So the Saudi argument might well be: why wouldwe sign and ratify the ICCPR, since we have our own document that is better attuned to our values? This answer will not, of course, satisfy the defenders of human rights who believe that liberal democracy is the universally correct form of government, not merely a western convention. When the UN expressed enthusiasm for the idea of an Arab Charter on Human Rights that was actually ratified by Arab states (as opposed to the earlier version of the charter in 1994, which had never been ratified), it did not thinkit would be a morally thinner document. The 2004 charter was initially drafted by a UN-appointed panel of Arab experts, using provisions from other human rights documents – including the ICCPR. But the Arab League dramatically edited it. As one scholar notes, “Fundamental changes were made that unfortunately rendered certain provisions of the Charter inconsistent with international law and important provisions were deleted.” Activists and scholars are particularly concerned by the Arab Charter’s approving invocation of the Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam of 1990, which explicitly subordinated all human rights to the requirements of sharia law; one scholar contends that this invocation makes the Arab Charter “a compromised document”. On the matter of freedom of speech, while the charter ensures “the right to information, freedom of opinion and freedom of expression, freedom to seek, receive and impart information by all means, regardless of frontiers” – language from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Article 32(2) adds this caveat: “Such rights and freedoms are exercised in the framework of society’s fundamental principles and shall only be subjected to restrictions necessary for the respect of the rights or reputation of others and for the protection of national security or of public order, health or morals.”

Whether we should deride such caveats, or regard them as necessary detours on the slow road to the liberalisation of the Arab world, remains the subject of debate. Many scholars argue that Islamic societies will only come to support liberal values when mainstream Qur’anic interpretation presents liberal democracy as flowing logically from fundamental Islamic tenets, and that this takes time.The “Arab awakening” may provide evidence to think that the “it takes time” argument is simply a handy excuse for Arab despots to say their people are not “ready” for democracy.

Regardless, by promoting the Arab Charter as an alternative vision to the ICCPR, and refusing to sign or ratify the latter, Saudi Arabia takes its place as a central defender of what (its leaders contend) Islam requires in politics. In so doing, it resists the vision of Saudi Arabia as a power unfit to lead the Muslim world, due to its excessively close ties to western governments – a vision that Iran is keen to promulgate.

(Additional research Jacob Amis)

reply report Report comment

@ThinkRights:

Really interesting question. Section 3(b) of Article 19 stipulates that “the protection of national security or public order” can justify restrictions on free speech rights, so long as the restrictions “are provided by law and are necessary”. Like so many provisions in international law, the use of the word “necessary” here is frustratingly vague (a predictable consequence of the fact that ICCPR was a negotiated agreement among numerous countries with divergent guiding political philosophies). “Necessary” will be, and has been, predictably interpreted by different countries in whatever way that facilitates their own restrictions on free speech. But let us suppose that a restriction is necessary if its enactment would, in fact, (a) impact a reasonably great majority of potential cases in which the permitted exercise of free speech would actually imperil national security by endangering lives or causing serious criminal harm and (b) would impact very few other kinds of cases. (I add this condition [b] since suspending all free speech rights on all topics, always, might be thought to yield considerable benefits for national security, as terrorist communications are a set of the total amount of communications; however, this would make the “necessary” condition far too weak to satisfy.)

So the question becomes: does the UK Terrorism Act satisfy these conditions? One worry stems from Part I, Section 1, in which the act stipulates that “a person commits an offence” of encouraging terrorism if “he publishes a statement to which this section applies or causes another to publish such a statement, and…at the time he publishes it or causes it to be published, he….intends members of the public to be directly or indirectly encouraged or otherwise induced by the statement to commit, prepare or instigate acts of terrorism or Convention offences; or…is reckless as to whether members of the public will be directly or indirectly encouraged or otherwise induced by the statement to commit, prepare or instigate such acts or offences.” It is the provision of “recklessness” that flags immediate alarm bells, and signals a worry that the act could be applied in such a way to violate condition (b) above. More specifically, it raises a worry that people engaging in such exercises as political satire could be held to have committed a crime under this act, despite the fact that it is unlikely they would, in fact, be seen as encouraging terrorism — and thus endangering national security — through their satire.

Making criminally liable those who recklessly fail to take precautions to ensure that the public will not construe their publications as encouraging terrorism obviously has its point; we do not want people in positions of influence to use ambiguous language when, for example, discussing a putatively unjust Western policy, and the putatively understandable character of terrorist acts committed in ostensible response to such a policy. People need to take care that they are not advocating terrorism. But is the brush too broad? Especially given the fact that internet publications count, might some immature blogger be criminally liable? Or should we trust legal authorities to make the right decisions?

reply report Report comment

I’m just wondering how this all fits with the UK Terrorism Act 2006 (pt1 s 3 relating to internet activity). Can limiting the fundamental right to freedom of expression in relation to “statements considered likely to be understood by some or all of the members of the public…as a direct or indirect encouragement or other inducement to them to the commision, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism” be justfiied in terms of national security?

reply report Report comment

@Essoulami and @Martinned:

Thanks to you both for your contributions. I did not include Western Sahara in the introduction precisely because of its disputed status in international law. Morocco does control most of the territory as a de facto matter, but many countries — more than 50 — recognize the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic as the rightful sovereign, though it only controls a small portion of the territory.

This issue raises the crucial matter of what Hannah Arendt called “the right to have rights”: the thesis that unless one has status as a legal subject within a particular recognized state, one cannot have any of the further protections that we take so seriously. Statelessness, on this view, is a fate we would not wish on our own worst enemy.

My question is whether this view is outdated. How crucial IS a state on this view to the protection of freedom of expression? We can think about this question by considering a familiar objection to international human rights practice. Critics of the ICCPR note that it lacks coercive bite: so long as we retain the familiar order of nation states, in which internal high courts are the last line of appeal, there won’t be any international enforcement mechanism unless states collectively cede that feature of their sovereignty. Of course, we do see innovations on this front, such as the European Court of Human Rights; however, while its decisions are usually complied with, the court does not yet have the power to itself strike domestic laws invalid. This raises the issue: even if our state is a party to the ICCPR, protecting free expression in such a state is not and never shall be something that can be outsourced entirely to legal authorities. It is the enduring responsibility of all citizens — in their families and religious organizations and civil society groups and businesses, here and there — to advocate tirelessly for its continued maintenance. And if THAT is true, what share of the burden even can the law carry? How important is the law to freedom of expression? Would be really interested to hear people’s thoughts.

reply report Report comment

And for the lawyers, just the actual free expression language of the ICCPR and the ECHR:

Art. 19 ICCPR:

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Article 10 ECHR:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

reply report Report comment

@Essoulami: That’s the Western Sahara, whose exact status under international law has been unclear for several decades. Most people these days tend to simply accept the reality on the ground and count it as a part of Morocco, but technically that is not correct.

reply report Report comment

Hi Jeff,

Congratulations for the good project you launched. I just have one question. Wich is the country in red in North Africa which has not ratified the CCPR? Mauritania has and also Morocco. Are you singling out Western Sahara which no a state at all to be party to any international convention? Please explain to me this red colour there and which you do not ention in your introduction.

All the best,

Said Essoulami