Sarah Glatte explores the potential and pitfalls of social media in combating sexism.

In early 2013, a heated debate ignited in Germany over the persistence of everyday sexism and misogyny. Its beginning coincided with the publication of an article in the Stern, a weekly news magazine. In the article, a young journalist, Laura Himmelreich, critically examined the political profile of leading German liberal politician Rainer Brüderle. Among other things, Himmelreich referred to public engagements at which Brüderle made sexually inappropriate comments, as well as to a late-night gathering in a hotel lobby at which he made sexual advances to her.

Soon after the article’s release, a student and blogger Anne Wizorek, called upon the online community to share their experiences of everyday sexism on Twitter under the hashtag #aufschrei (“outcry”). The response was immediate and overwhelming. Within 6 days, over 15,000 users had posted more than 49,000 comments on the topic, a record for Twitter activity in Germany. Never before had a single topic been so widely discussed among German members of the social networking site. With an estimated 2.4 million active users, Twitter exposure is relatively weak in Germany, compared to the UK’s 6.6 million and the US’s 22.9 million users. In spite of this, #aufschrei sparked a national debate. After only a few days, the issue of sexism was discussed at length in mainstream German media with virtually all major German newspapers and TV channels reporting on the topic.

In the course of what is now known in Germany as the Sexismus Debatte – sexism debate, Twitter revealed itself to be both a blessing and a curse for free speech. It has been a blessing because it has provided a platform for thousands of citizens to discuss sexism and to raise awareness on the widespread nature of this problem. Had it not been for the impulse provided by Twitter users, the debate would not have received such extensive and lasting attention. Campaigns similar to #aufschrei have been launched in other countries too. The Everyday Sexism Project is a successful example of an online initiative set up in the UK to encourage men and women to share their ‘routine experiences of prejudice and harassment’ (on Twitter under #everydaysexism). Both the Everyday Sexism Project and #aufschrei illustrate the potential for media 2.0 to encourage free speech and public discourse within and across national boundaries. Nevertheless, the campaigns also highlight the problems and pitfalls that come with the possibility of instantly expressing and sharing opinions with thousands of others. As one German Twitter user wrote:

“For one #aufschrei, there are three blocked sexist [comments].”

The curse of social networking sites and online discussion forums for free speech lies in the fact that they also provide a platform for hate speech and cyber-bullying. After being publicised by mainstream media as the initiator and face behind the #aufschrei campaign, Anne Wizoreck became the focus of a series of sexual insults and threats. Although anyone can become the target of such cyber-bullying, it is young women participating actively in political life or expressing their opinions on social (and feminist) issues who are particularly affected. Julia Schramm, a member of the German pirate party, started a blog to document various hateful and threatening messages she received after the publication of her book which she, against the principles of her party, did not make freely available on the internet. In the UK, Louise Mensch, former conservative MP, similarly became the object of a wave of online abuse (mainly via Twitter) including sexist insults and violent threats in mid-2012 after her appearance in the British news show Newsnight. These examples show how hate speech directed against women often involves comments and insults that are sexually degrading or threatening in character. There appear to be far fewer cases of men being subjected to similarly explicit sexist online attacks.

The response chosen by Wizorek, Schramm, and Mensch has been to openly criticise such forms of cyber-bullying. But this is the exception rather than the rule. Susanne Patzelt, moderator of an online forum for the German feminist magazine Emma, writes that more than anything, sexist comments and threats against women in online forums serve to stifle discussion, because they discourage users from participating altogether. For the majority of those who post hostile messages, she argues, the aim “is not to express a controversial opinion, but to ruin the dialogue by enforcing their own rules and topics.” Once posted, insults and degrading comments can reach an audience of millions and undermine the reputation and integrity of those they are targeting.

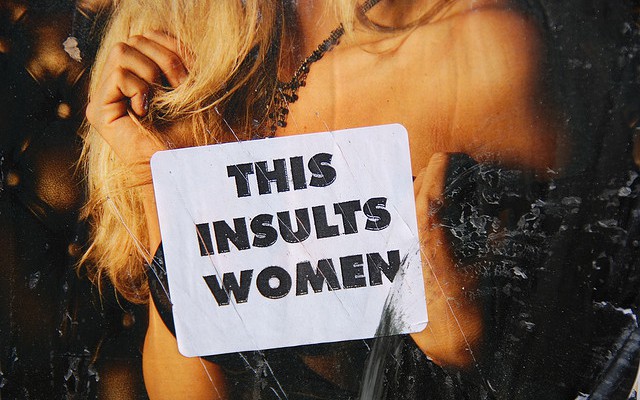

The ability to conceal one’s online identity through use of pseudonyms (the very aspect that facilitates free speech in countries where it is otherwise restricted) appears to lower the inhibition threshold of many internet users. The internet has thus become a medium through which sexism, misogyny, hate and violence against women can flourish. We do not even have to look at the thousands of freely available pornography pages to realise that online sexism is everywhere: sites where users rate the sexual attractiveness of women, sites where men share nude images of their ex-partners without their consent and, most worryingly, popular social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter which tolerate the dissemination of comments and images glorifying sexism, rape and domestic violence. Laura Bates, founder of the Everyday Sexism Project, rightly argues that we must take a more critical stance on occurrences of sexual assault online, because of the cultural norms it promotes: “Each [sexually violent] image normalises gender-based violence, sending the message to both victims and perpetrators that ours is a culture that doesn’t take it seriously.”

There are a number of steps that can be taken in response to online sexism and abuse. First and foremost, it is our responsibility as users to report sexist hate speech. Openly criticising such instances not only helps to spread the message that this conduct is unacceptable, it also increases the pressure for online administrators to remove harmful content in fear of reputational damage. Secondly, we must demand greater vigilance to be shown on the part of those who regulate Facebook, Twitter, and similar sites. It can be helpful too to alert companies, if their products are being advertised next to sexist or racist images or comments. This has been one of the strategies pursued by the Everyday Sexism Project and it has already led to remarkable achievements, including a pledge from Facebook itself to review its guidelines and policy on sexist hate speech.

At the same time, there are limits to how much change individual users and even popular online campaigns can realistically bring about. We must therefore discuss with ever greater urgency how the distribution of harmful content on the internet should be regulated by law. We cannot and should not avoid such discussions on the grounds that they might lead to the infringement of online free speech. People must be held accountable for their actions – offline as well as online. Ridicule, threats of sexual violence, and bullying pose a far greater threat to free speech than the imposition of online community standards and the censoring of sexually degrading images. In Germany, as elsewhere, clear guidelines on how to prosecute online offences are unfortunately still mostly non-existent.

It is ironic and poignant that the German #aufschrei campaign has added further cases of sexist slander against those who have voiced their opinions on the topic. Nevertheless, the campaign and the ensuing public debate have helped to raise awareness about a problem of sexism and misogyny that is still acutely felt by millions of men and women. If nothing else, it has heightened Germans’ sensitivity towards the issue. Our global online community is in need of a similar wake-up call.

Update: The #aufschrei campaign on Twitter has been awarded the prestigious Grimme Online Award 2013 for its role in initiating a society-wide discussion (online and offline) on the problems of everyday sexism in Germany.

Sarah Glatte is a doctoral candidate in politics at Wadham College, Oxford. Her research explores the relationship between political participation and gender culture in unified Germany.

reply report Report comment

I stumbled over this text today although it’s nearly 2 years old, but s still want to comment on a few things.

On reading the subheadline “potential and pitfalls of social media” I expected a way more critical approach to #aufschrei, because there are many pitfalls to be explored here but the text addresses none of it: First, the claim, “over 15,000 users had posted more than 49,000 comments on the topic” is way over the top: A statistical analysis of a sample indicated that only a very small part of the tweets – 1,7 % !! – was actually “on the topic”. The rest was anti-feministic (27 %), related to newspaper articles (32,5 %), Spam or repetition. (see: http://www.bpb.de/apuz/178666/tausendschoen-im-neopatriarchat). A second problem: People actually hurt by something usually don’t like talking about it in public, while people who are merely disgusted do this freely: Moreover, #Aufschrei mixes “sexism” with “sexual violence”: “Invisible” sexism like not-getting-your-Job because of your Gender does not show up at #Aufschrei, while a severe sex crime committed by a mentally ill person without any ideology at work is suddenly an example for “everydaysexism”. For these reasons the picture the campaign painted about “what’s going on” was systematically off: Truly severe incidents of sexism tend to be underrepresented while everyday events that enrage people who are easy to enrage are overrepresented. — To me, #Aufschrei is a media-fake.

As for the persons mentioned: Both Julia Schramm and Anne Wizorek are highly controversial figures in german Twitter-Discussions. Schramm (no longer member of the pirate party) is infamous for highly provocative speech like the Glorification of Atrocities during WW2 (Stalingrad-Battle or the “area Bombardement” of german Cities like Dresden). A member of the “anti-german” movement, Schramm also tweeted, she wanted “to spit on Steinmeier [german Foreign minister] for his nationalistic shit”. Anne Wizorek advocated last year to “No-Platform” a well known Techblogger who fell out with another net-feminist.

— So, if you want to defend free speech, these people are definetely not in your camp.

reply report Report comment

Thank you Sarah for raising this issue! I agree that we must not shy away from calling out online users on sexist or other forms of hate speech. At the same time I would like to suggest that we need to consider the issues you raised within the wider context of sexism in the media. In my opinion free speech comes with the responsibility to report in a fair and respectful manner. After all, if the big German daily newspapers such as the BILD only ever report on women as sex objects it can hardly surprise that online users feel emboldened to shout down women on social media or engage in other forms of sexist speech.

reply report Report comment

A really interesting spin on the #aufschrei campaign. One “advantage” of such hate campaigns on social networks appears to be that there is some form of record of it, which – even if the users are anonymous – makes it possible to make a larger audience aware of the extent and gravity of the problem. Still, probably a rather small consolation…