Der Prozess gegen den kenianischen Radiomoderator Joshua Arap Sang wirft grundlegende Fragen zum Zusammenhang zwischen Worten und Gewalt auf. Katherine Bruce-Lockhart berichtet.

Als Hassrede (aus dem Englischen „hate speech“) bezeichnet man Äußerungen, die andere Menschen aufgrund deren Zugehörigkeit zu einer bestimmten Gruppe diskriminieren. Solche Äußerungen bereiten Gesetzgebern schon lange Kopfschmerzen, denn sie stellen die Grenzen der Meinungsfreiheit in einer Gesellschaft ständig neu infrage. Debatten zum Thema Hassrede bestimmen regelmäßig die Schlagzeilen. Auf unserer Seite finden sich zu diesem Thema Artikel über die Westboro Baptist Church, die bei Militärbegräbnissen gegen Homosexuelle demonstriert oder zum Lied „Erschießt die Buren“, das in Südafrika vom damaligen Vorsitzenden des Jugendverbandes der Regierungspartei, des Afrikanischen Nationalkongresses, öffentlich wiedergegeben wurde. Obwohl solche Fälle von Hassrede immer schwer beleidigend sind, lösen sie nicht unbedingt Gewalt aus. Darum versuchen Experten die sich mit der Meinungsfreiheit auseinandersetzen zunehmend, Hassrede von „gefährlicher Volksverhetzung“ zu unterscheiden. Dabei definiert man „gefährliche Volksverhetzung“ als „Aussagen, bei denen der begründete Verdacht besteht, dass sie Gewalt einer Gruppe gegen eine andere auslösen oder verstärken.“ Um die Gefährlichkeit von Aussagen einschätzen zu können, hat die Politikwissenschaftlerin Susan Benesch fünf qualitative Schlüsselvariablen aufgestellt, die uns helfen, Vorfälle von Hassrede zu untersuchen. Zu den Variablen in Beneschs Model gehört der Einfluss des Sprechers in der betreffenden Gesellschaft, die Sorgen und Ängste der Zuhörer, der soziale und historische Kontext, das Medium, durch das die Äußerungen verbreitet werden sowie die Frage, ob die Äußerungen als Aufruf zur Gewalt verstanden werden können oder nicht.

Sowohl Ruanda also auch Kenia haben in den vergangenen zwei Jahrzehnten eine erhebliche Menge an Gewalt erlebt. Sie können uns daher als Fallbeispiele dienen, um zu erörtern ab wann und auf welche Art und Weise Hassrede zur Gefahr wird. So ist die Rolle, die der Radiosender Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (Radio RTLM) in der Aufhetzung zum Völkermord in Ruanda spielte, umfassend dokumentiert und bei den verleumderischen Äußerungen auf dem Sender handelte es sich eindeutig um Hassrede. „Der Radiosender ermutigte die Menschen, sich an dem Völkermord zu beteiligen, indem er verkündete: ‚die Tutsi sind eure Feinde,’“ bemerkt ein Überlebender des Genozids. „Hätte der Sender nicht solche Botschaften verbreitet, dann hätten die Menschen nicht solche Gewalttaten verübt.“

Statistiken, die belegen, dass die Beteiligung der Bevölkerung am Genozid gegen die Tutsi durch das Aufhetzen des Senders RTLM anstieg, bestätigen diese Beobachtung. Um den Einfluss von Radiosendungen auf die Teilnahme an Gewalttaten zu ermitteln, verwendete David Yanagizawa-Drott, ein Politikwissenschaftler an der Universität Harvard, in seiner Studie zu dem Völkermord in Ruanda Statistiken über Gewalttaten in mehr als eintausend Dörfern. Für Wissenschaftler, die Hassrede erforschen, sind die Ergebnisse seiner Forschung von wegweisender Bedeutung. So stieg in Regionen, in denen die Bevölkerung uneingeschränkten Radioempfang hatte, die Anzahl der Gewalttaten, die von Zivilisten verübt wurden, um 65%. Organisierte Gewalttaten stiegen sogar um 77%. Yanagizawa-Drott schätzt, dass insgesamt etwa neun Prozent der Opfer des Völkermords, bis zu 45.000 Tote, Gewalttaten zum Opfer fielen, zu denen Radio RTLM aufgerufen hatte. Diese Statistiken verdeutlichen, wie schnell aus Worten Taten werden und welch fatale Auswirkungen Volksverhetzung für Menschen in Bürgerkriegsregionen haben kann.

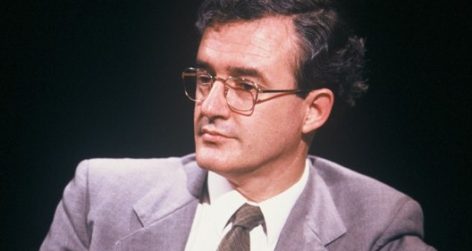

Wenn wir diese Gefahr bannen wollen, dann müssen wir die Täter zur Verantwortung ziehen. Dazu müssten wir jedoch konkret nachweisen können, dass die betreffenden Aussagen Gewalttaten ausgelöst haben. Für solche Verfahren gibt es durchaus historische Präzedenzfälle. So sprachen die Richter des Internationalen Strafgerichtshofes für Ruanda Mitarbeiter des Senders RTLM des Vorwurfes schuldig, „explizit zur Auslöschung der ethnischen Gruppe der Tutsi“ aufgerufen zu haben. In dem Prozess gegen den kenianischen Radiomoderatoren Joshua Arap Sang verhandelt auch der Internationale Strafgerichtshof (IStGH) derzeit den ersten Fall von gefährlicher Volksverhetzung. Sang war einer der vier Kenianer, gegen die der IStGH im Zusammenhang mit der weit verbreiteten Gewalt im Land nach den Wahlen in den Jahren 2007 und 2008 ein Verfahren wegen Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit eröffnete. Für alle, die sich mit der freien Meinungsäußerung beschäftigen, ist der Fall besonders interessant, da Sang als Moderator für Kass, einen Radiosender in der Sprache der Kalenjin, arbeitet. Damit ist er in diesem Kontext der einzige Angeklagte, der kein Politiker ist (sowohl der derzeitige kenianische Präsident Uhuru Kenyatta als auch Vizepräsident William Ruto wurden ebenfalls angeklagt). Ihm werden Mord, Deportation oder Zwangsumsiedlung der Bevölkerung sowie Verfolgung vorgeworden.

In dem Prozess gegen Sang, der am 28. Mai 2011 beginnen sollte, lautet die entscheidende Frage, ob es dem IStGH gelingen wird, eine Korrelation zwischen Hetzreden und Gewalttaten nachzuweisen. Nach Beneschs Kriterien ließen sich Sangs Äußerungen in mehreren Hinsichten als Volksverhetzung einstufen. Als Radiomoderator besitzt Sang erheblichen Einfluss auf die Bevölkerung der Kalenjin. Seine Sendung erreicht täglich ein Publikum von viereinhalb Millionen Zuhörern in Kenia sowie vielen weitere Zuhörern in der Diaspora. Zudem einte viele seiner Zuhörer die Sorge, die Wahlen im Land seien zum Nachteil von

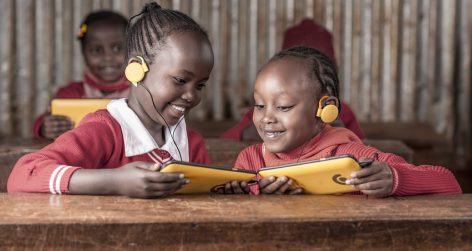

Raila Odinga, dem Kandidaten, den die meisten Kalenjin unterstützen, verfälscht worden. Wie die Anklage darüber hinaus argumentiert, lassen sich Sangs Äußerungen als Aufruf zur Gewalt verstehen. Demnach wird er mit solch Äußerungen wie „Der Krieg hat begonnen“ und „das Volk der Milch“ sollte „das Gras mähen“ in Verbindung gebracht. Diese umgangssprachlichen Ausdrücke beziehen sich auf die Unterschiede zwischen den Kalenjin (der ethnischen Gruppe, der Sang angehört und die traditionell Kuhhirten sind) und den Kikuyu (der ethnischen Gruppe, die von Sangs Unterstützern angegriffen wurden). Vor dem Hintergrund, dass es in Kenia bei jeder Präsidentschaftswahl seit 1992 zu Gewalttaten gekommen ist und sich Kalenjin und Kikuyu schon lange über Ländereien streiten, stieg die Gefahr eines Gewaltausbruches stetig an. Hinzu kommt, dass das Radio in Kenia ein mächtiges Kommunikationsmittel ist, das Nachrichten in den verschiedenen Dialekten verbreitet und damit für Menschen, die weniger gebildet sind oder die in dörflichen Regionen leben, leichter zugänglich ist als andere Medien.

Auch wenn Sangs Fall damit augenscheinlich in die Kategorie der Volksverhetzung fiel, war der Ausgang seines Prozesses ungewiss. Im Gegensatz zu dem Fall des Radiosender RTLM in Ruanda blieben von den Sendungen auf Kass während der Wahlen nur wenige Mitschriften erhalten. Laut den Informationen von Human Rights Watch wurden die verleumderischen Aussagen zudem hauptsächlich von Gästen der Sendung statt von Mitarbeitern von Kass getätigt, was es bedeutend schwieriger macht, den Schuldigen für die Hetzreden festzustellen. Unterdessen ist Sang von seiner Unschuld überzeugt und beruft sich zu seiner Verteidigung auf das Prinzip der freien Meinungsäußerung. Sang argumentiert, dass seine Verurteilung der Meinungsfreiheit erheblich schaden könnte. In Radio Propaganda and the Broadcasting of Hatred (2012) zitiert Keith Somerville Sang mit den Worten: „Wenn sie mich in Den Haag vor Gericht stellen, obwohl ich davon überzeugt bin, dass ich lediglich meinen Beruf ausgeübt habe, was werden sie dann Journalisten sagen?“ Höchstwahrscheinlich wird der Ausgang des Prozesses gegen Sang die journalistische Freiheit der Radiostationen in den verschiedenen Dialekten Kenias maßgeblich beeinflussen sowie zu unserem Verständnis von den Auswirkungen von Volksverhetzung in Konfliktregionen beitragen.

Um den Unterschied zwischen Hassrede und gefährlicher Volksverhetzung klarer herauszuarbeiten, benötigen wir letztendlich mehr Nachforschungen und mehr Debatten zu dem Thema. Ob in Ruanda, Kenia oder in anderen Ländern, die unlängst von Gewaltausbrüchen erschüttert wurden – es ist unabdingbar, dass wir die Rubrik der volksverhetzenden Äußerungen eindeutiger definieren. Auch wenn die Frage, wann, warum und auf welche Art und Weise Worte Gewalt auslösen noch so schwer zu beantworten ist – sie ist von grundlegender Bedeutung sowohl in Debatten zur Meinungsfreiheit wie auch für unser Bestreben, Gewalt in Zukunft zu verhindern.

Katherine Bruce-Lockhart ist Stipendiatin des Dahrendorf-Programms. Sie studierte im Master MSc African Studies am St. Antony’s College, Oxford. Zuvor arbeitete sie als Journalistin in Kanada und Südafrika sowie als Forscherin und Programmiererin für Nichtregierungsorganisationen, die sich mit der Meinungsfreiheit beschäftigen, in Namibia, Nepal und Kanada.

reply report Report comment

Dear Ms. Bruce-Lockhart,

In our IB English Language and Literature course, we have been discussing the complex issue of freedom of expression. We realize that the borders between hate speech and dangerous speech are obscured and muddled. We believe that, although these two specific cases demonstrate dangerous speech and should be punishable by law, we should be careful not to

sacrifice the right to express our opinions, as seen in the case of Geert Wilders.

Of Susan Benesch’s five key qualitative variables, perhaps the most important one is “whether or not the speech act is understood as a call to action.” We believe that this is pivotal in separating utterances into those that should be punishable, and those that should be protected by the ideals of free speech. In her paper “Dangerous Speech: A Proposal to Prevent Group Violence”, Benesch goes into more detail about how to judge this criterion:

Did the speech describe the victims-to-be as other than human, e.g. as vermin, pests, insects or animals?

Did the speech assert that the audience faced serious danger from the victim group?

Did the speech contain phrases, words, or coded language that has taken on a special loaded meaning, in the understanding of the speaker and audience?

In Kenya, Joshua Arap Sang used his radio show Le Ne Emet, to communicate with the native Kalenjin and to spread hate messages against the Kikuyu, Kambas and Kisiis, such as:

“the mongoose is at the chickens”

“the people of the milk should clear the weeds from the grass”

Sang instructed listeners to burn properties in Eldoret belonging to non-Kalenjins by saying, “let’s not destroy our own”

Sang’s language shows how he monitored the violence through these coded metaphors. It seems to fall under all of Benesch’s criteria to be classified as dangerous speech. The victimized minorities are referred to as weed that must be cleared. Sang makes it clear for the Kalenjins that they are the “people of the milk” that need to take action against Kikuyu, Kambas and Kisiis, by destroying their property for example.

We agree that “perpetrators of dangerous speech must be held accountable”, but although Sang’s discourse seems to fall under the category of dangerous speech, the results of his ongoing trial in the ICC remain far from definite. Language surely can incite violence, but the complex nature of dangerous speech, having these shady borders, makes judging it a difficult task.

Contrast this to the case of Geert Wilders, a Dutch right-wing politician who was recently acquitted of inciting hatred against Muslims. According to Wilders, “Islam is not a religion, it’s an ideology, the ideology of a retarded culture” and “the Koran is a fascist book which incites violence. That is why this book, just like [Adolf Hitler’s] Mein Kampf, must be banned.” This is where the boundary of hate speech and dangerous speech becomes highly debatable.

Wilders does not specifically launch an attack on Muslims, but on their religion and their culture. According to him, “It’s not my intention to have anything at all to do with violence. On the contrary, I despise violence – I just want a debate.” His call to “get rid of that woman-humiliating Islamic symbol” (the veil), cannot be classified as a call to violence.

So it is clear that Wilders does not fall under what Benesch calls ‘dangerous speech’. But is he not provoking discrimination against Muslims? We believe that Wilders has the right to express his opinion, even if we might not agree with it. If Wilder’s actions become punishable by law, the slippery slope may continue, and the whole notion of free speech will be jeopardized. In Wilder’s words, “I am on trial, but on trial with me is the freedom of expression of many Dutch citizens”.

On the other hand, in the Rwandan case, some phrases that were broadcasted by the RTLM transcend the blurry margin and are obviously dangerous speech:

“You have to kill [the Tutsis], they are cockroaches…”

“All those who are listening to us, arise so that we can all fight for our Rwanda… Fight with the weapons you have at your disposal… We must all fight [the Tutsis]; we must finish with them, exterminate them, sweep them from the whole country… There must be no refuge for them, none at all.”

“I do not know whether God will help us exterminate [the Tutsis] …but we must rise up to exterminate this race of bad people… They must be exterminated because there is no other way.”

This ticks all of Benesch’s boxes. Undoubtedly, freedom of speech should not allow these crimes against humanity to go unpunished, and we believe that the life sentences that some of the members of RTLM were given are just.

Although we agree that “to prevent dangerous speech, perpetrators must be held accountable”, we always run the risk of giving over to the emotional sensibilities of the victims and restricting freedom of expression to save them from discrimination rather than bodily harm. It is difficult to draw boundaries on what should and should not be allowed, and Benesch’s variables do help, but in order to protect the ideals of freedom of expression, it is essential that these boundaries are agreed upon soon, before the slippery slope continues.

Sincerely,

A. Serbetsoglou, A. Strating, E. Zomer

reply report Report comment

Dear A. Serbetsoglou, A. Strating, E. Zomer,

Thank you very much for your comments. As you point out, some cases of dangerous speech are much more clear cut that others. The role of RTLM in the Rwandan genocide is certainly one of the clearest cases of dangerous speech, while those of Sang and Wilders are more contested. Sang’s trial at the ICC is a very important test of the boundaries of dangerous speech, and it will be interesting to see how his defence and the prosecution against him unfold. Ultimately, as you suggest, more clear boundaries between hate speech and dangerous speech are necessary, both to protect freedom of expression and to prevent violence.

You can find more on the Wilders case on the website: http://freespeechdebate.com/en/case/geert-wilders-on-trial/

reply report Report comment

Many thanks for this very thoughtful comment. We will pass it on to Katherine Bruce-Lockhart, who I hope will feel able to respond.

reply report Report comment

Hello there Mrs. Katherine Bruce-Lockhart,

We are a group of students in an English language and literature class currently working on language and taboo. We have read your piece and we agree with the main points. We believe that there is indeed a thin line between free speech and hate speech but we too are struggling with determining how, when and why hate speech “serves as a springboard to violence.” However a point raised during our discussion was about how you draw the line between hate speech and dangerous speech.

You define dangerous speech as speech that incites violence against a group and hate speech as speech that denigrates people on the basis of their membership in a group. That raises the questions then: should dangerous speech be punished when it does not incite violence? Or would that just be considered as hate speech? However hate speech could also hurt a person or a group of people to the point that they commit suicide. Take the case of eleven year-old Carl Joseph Walker-Hoover, who killed himself after enduring months of anti-gay bullying at his school in Springfield, Massachusetts. Should that form of hate speech be punished?

We believe that dangerous speech always starts with forms of hate speech and if restrictions were applied on hate speech, we could prevent it from developing into

dangerous speech that incites violence and provokes deaths. One could argue that the Rwandan genocide could have been prevented if the ICC had stepped in when the hate speech towards the Tutsi’s began. Therefore from the very start of the conflict, where the media was dehumanizing the Tutsi’s or the Kalenjin people by using statements such as “cut the grass” or calling them names such as cockroaches (‘inyenzi’).

‘If the radio had not declared things, people wouldn’t have gone into the attacks”

If hate speech aims to attack the reputation of a person or group of people, than most forms of hate speech are indirectly promoting violence and should be classified as forms of dangerous speech.

How far do free speech laws go in protecting people that are spreading hate speech? You can’t really make laws that deny people expressing their opinions.

You argue that dangerous speech should be analyzed by looking at factors such as the level of a speaker’s influence, the grievances of the audience, whether or not the speech is understood as a call to violence, the social and historical context and the way in which the speech is disseminated. But how do you determine whether or not a speaker has enough influence to affect action, and when looking at factors to do with those listening to the speech, we consider it impossible to make a generalization because different people will have different views.

The fact that we can not make a generalization is supported by the fact that different countries have different legal views on hate speech. Kenan Malik, describes the inconsistency of the hate speech laws in different countries: Britain bans abusive, insulting, and threatening speech. Denmark and Canada ban speech that is insulting and degrading. India and Israel ban speech that hurts religious feelings and incites racial and religious hatred. In Holland, it is a criminal offense deliberately to insult a particular group. Australia prohibits speech that offends, insults, humiliates, or intimidates individuals or groups. Germany bans speech that violates the dignity of, or maliciously degrades or defames, a group. And so on. In each case, the law defines hate speech in a different way.

Here in The Netherlands, a quite controversial debate went on in 2011. Stated in a BBC news article, far-right politician Geert Wilders, who described Islam as „fascist“, was acquitted of inciting hatred against Muslims. According to the judge, Wilders’ comments on comparing the Koran to Hitler’s Mein Kampf were „acceptable within the context of public debate.” Although the speeches given by this political figure have said to have caused increasing hatred and violence towards the Islamic society in the Netherlands,

the Geert Wilders trial is an example of how people in the Netherlands have recently become more tolerant of differences in opinions. This allows people to express how they feel about specific things but can also be harmful to certain groups as it allows expressing hate towards a social group. Only the police and the queen are protected against any forms of hate speech.

Therefore we have come to believe that hate speech is a form of free speech. However there should be clear line between hate speech and dangerous speech, and we should apply restrictions to all forms of dangerous speech. Even though hate speech also incites violence we believe that there must be a difference between the two and in order to determine this difference we need to look at the specific factors.

We hope to get a favourable response from you!

Your fellow readers.

reply report Report comment

Thank you very much for your comments and discussion of these important issues. You raise some of the key quandaries in the debates on hate speech and dangerous speech that have yet to be fully answered. As you discuss, there is not a universally recognized definition of dangerous speech, and the understanding of dangerous speech changes greatly depending on the socio-historical context. In the cases I examined, the type of speech employed was arguably ‚dangerous speech‘ using Benesch’s criteria. I find her framework very useful, but it is one approach and certainly other approaches can be explored. More work is needed to define what exactly constitutes dangerous speech and how it is different from hate speech.

I recommend that you look at this video of a United Nations panel on the topic of dangerous speech. It raises many interesting questions about the differences between hate speech and dangerous speech, and also examines how we should limit dangerous speech in order to prevent violence. http://www.worldpolicy.org/blog/2013/02/06/lets-talk-about-genocide

reply report Report comment

Hello, we are three students from the American School of the Hague taking a Language and Literature course. We have currently been studying hate speech and taboo, and we’re interested in exploring the influence of the social-historical background of a country and how it allows hate speech to become dangerous speech. Hate speech should therefore be persecuted, during periods in which a country is experiencing severe grievances and the speech calls for direct action against a particular group.

This applies to the case of Kenya in 2007. After the country’s presidential elections in late 2007, in which the winner was Mwai Kibaki of the Party of National Unity (PNU), violence spurred between PNU supporters and the Orange Democratic Movement supporters (ODM). At this time, Kenya was experiencing high crime rates. Stated from The New York Times, gangs were forcing their way into homes “dragging out people of certain tribes and clubbing them to death,” as the ODM’s supporters believed the election had been rigged against their leader. This intense tension between the political and ethnic groups created fertile ground for the outbreak of violence.

Joshua Arap Sang, the KASS FM radio broadcaster, is in trial in the International Court of Justice in The Hague, along with William Samoei Ruto, the Deputy President of Kenya, for crimes against humanity. Sang is a quintessential player in the 2007-2008 Kenyan crisis and is convicted of spreading hate messages, broadcasting false news to incite the Kalenjin people. Sang is an ODM supporter, and Ruto used Sang’s role as a radio broadcaster to collect supporters and to create codes so Sang’s listeners would know when to attack the rival ethnic group, Kikuyu. The ICC has charged Sang and Ruto of crimes against humanity in three subtopics: murder, forcible transfer of people, persecution of an ethnic and political groups and crimes of rape and sexual abuse.

Sang’s role in the Kenyan crisis has parallels with Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda in Hitler’s Third Reich. There seems a direct correlation between Hitler’s rise to power and the socio-economic despair that Germany experienced due to the Great Depression, according to historian Robert Gellately. Goebbels exploited the social and economic situation through means of film, art, posters, etc, to rally support for the Nazi Party and hence the support for their anti-Semitic cause, just as Joseph Sang used his radio to gather support for the ODM and hatred for the PNU. Both reached a desperate population that incited them to target their rivals.

Goebbels, an avid supporter of the Nazi Party, was in charge of modern propaganda to rally support but also galvanize anti-Semitism. In fact, Goebbels’ propaganda program incited Kristallnacht, where Jews were purged from German society and synagogues were destroyed. Furthermore, Goebbels used film to make the most anti-Semitic movies, increasing the hatred of the Jewish population and thus making the German population accept and encourage the deportation and deaths of six million Jews.

Both Goebbels and Sang used a scapegoating technique where they targeted an ethnic population and blamed them of all the problems people which they were facing. In Germany, the Jews were blamed for the start of the Great Depression, and were labeled as rich people while the rest were suffering extreme poverty. In Kenya, the Kikuyu were dominant in politics and so the Kalenjin held them accountable for everything that was wrong. Scapegoating creates abhorrence for a targeted population which makes it easier to incite violence towards them. This is what exactly occurred in both the Third Reich and in Kenya in 2007.

Sang’s radio station RTLM, gained an audience of four and half million quotidian Kenyan listeners. Amnesty International states that Eldoret, where his radio was based, “was a scene of some of the worst bloodshed”.

Coincidence? We think not.

Audience plays a major role in hate crime. This influences the switch from hate speech to dangerous speech because it allows for words to morph into action. As the ICC’s official statement puts it, “Sang was using his radio program to collect supporters and provide signals to member of the plan on when and where to attack,” especially targeting citizens who didn’t have access to other forms of media. This allows for RTLM to give a biased view to the people who are less educated, as Katherine Bruce-Lockhart says.

Yes, Sang will argue that he can’t be convicted under free speech but he is using language to manipulate his audience, ultimately turning them to violence. This seems more plausible in a nation that suffers from interethnic rivalries.

Hate speech will turn into dangerous speech when the social and historical context calls for it. Sang exploited popular discontent among the Kalenijn ethnic community (whom supported ODM) and took advantage of this troubled social situation to encourage aggression against the PNU supporters. He used his radio to clearly organize the crime and rally up supporters – a manifestation of his deliberate intention to incite violence.

reply report Report comment

Thank you very much for your comments. It is certainly important to consider historical examples of dangerous speech and the case of Goebbels and Nazi propaganda is an extreme one. At this point, we know much more about the extent of dangerous speech in Nazi Germany than we do in Kenya. As Sang’s trial unfolds, we will hopefully understand more about his role in the post-election violence. Certainly, his case is less clear cut than that of RTLM in the Rwandan genocide and the use of propaganda in Nazi Germany.

reply report Report comment

The Thin Line Between Hate Speech and Dangerous Speech

We are three students high school students in the I.B SL Language and Literature class studying the implications of hate speech.

The difference between hate speech and dangerous speech has been an increasing discussion topic as we become more aware of the power of language, and its dangers. Katherine Bruce-Lockhart states the difference between hate and dangerous speech and how determining that difference is pivotal in bringing offenders to justice. Dangerous speech leads to horrible acts of violence as seen in the Rwandan Genocide, where it is estimated that around forty-five thousand deaths were incited by the speeches broadcasted by Radio RTLM. The problem is that in many cases it is not so clear whether it is dangerous speech or just hate speech because of the difficulty in defining dangerous speech. It is that difficulty that makes the prosecution of perpetrators of hate or dangerous speech so difficult, as seen in Joshua Arap Sang’s ongoing trial. The difference of dangerous speech and hate speech is more complicated than what the article suggests, thus making it more difficult to set legal boundaries to bring perpetrators of such acts to justice.

The article expresses dangerous speech as “speech that has a “reasonable chance of catalyzing or amplifying violence by one group against another.” The differences that they decided differentiates one from another is one whose connotations imply violence. When looking at how the article distinguishes hate speech from dangerous speech, they do not take into account the context and the meaning that is behind the speech. In the case of athletic chants, the boundaries that the article set do not fit. The words that may be used in some chants, the word’s connotations may “ amplify violence”, however, the denotation do not. As seen in the example of a game between Notre Dame ( The Fighting Irish) and North-Western (Wildcats), the Wildcat fans were chanting “ Kill the Fighting Irish, kill the Fighting Irish”. The denotation of the work “kill” is to cause death however in the context its meaning does not imply violence of any kind.

The Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) has been gaining notoriety as news spread of their picketing of funerals of U.S soldiers, politicians and even children. WBC protesters stand outside holding signs with the words”Thank God for IEDs”, “You are going to hell”, “Pray for more dead soldiers”, “Thank God for dead soldiers”. The message that WBC conveys is one of complete hatred towards homosexuals and of those who accept them, their protests have been so hateful, so offensive that hundreds of thousands of people have brought their protests up to the Supreme Court in the hope that something will be done to stop the protests. WBC protesters are clearly engaging in hate speech, but because it doesn’t incite violence or create a dangerous situation it is not considered dangerous speech, and therefore are not doing anything illegal. We believe that the protests have no objective other than to offend and insult those who support homosexuals, and therefore those WBC protesters should not be protected by the 1st amendment and be held against the law.

We understand how difficult it is to legally set laws that prohibit dangerous speech. People interpret things in different ways which would make the laws that are placed, subjective rather than objective. There should be no legal boundaries put on hate speech, since it goes against the right of free speech. Also, when laws do prohibit hate speech, certain people might interpret the hate speech differently. However, there is an exception. Speech that causes imminent danger or speech that leads to someone taking dangerous action could and should have legal boundaries.

When laws are created that ban other forms of hate speech, it does not reduce or eliminate that hate speech, it does the opposite. Kenan Malik says, “ you cannot reduce or eliminate bigotry simply by banning it.” The example he uses to support this is the example of Britain prohibiting incitement to racial hatred in 1965. When the Race Relations Act was passed, the next decade in British History was the most racist in British history, despite the fact that racial hatred was prohibited. When Britain’s laws were revoked and time had passed, racism decreased. This is because of the social changes that happened. Another example that supports Kenan Malik’s argument is the Westboro Baptist Church. Many countries have banned the bigotry that the Westboro Baptist Church uses, yet they continue to do it. The Westboro Baptist Church members are banned from entering both Britain and Canada because of their bigotry, but they keep picketing at places such as public funerals.

In the case of Snyder v. Phelps (Phelps is the leader of the Westboro Baptist Church) the Supreme Court of the United States has ruled that speech on a public sidewalk, about a public issue, cannot be liable for a tort of emotional distress. They made this ruling because the WBC’s protests do not explicitly cause imminent danger nor are their protests calls to a dangerous action. The WBC’s protests are considered hate speech, not dangerous speech. This supports that people interpret hate speech differently and laws that are imposed on free speech become subjective. That is why legal boundaries should not be imposed on speech unless it causes imminent danger or is a call to a dangerous action.

The article’s idea that dangerous speech is one that incites violence towards others is over simplistic as it does not take into account the context and connotations of the speech. During the game Notre Dame against North-western the fans who shouted the chant would be considered criminals according to the article, which is quite ridiculous. The chant is clearly not a call to violence towards the opponents, but rather an attempt to support their team. The difference between hate and dangerous speech is so small, making it really difficult to define.

reply report Report comment

Thank you very much for your comments. It is certainly true that defining the boundary between hate speech and dangerous speech is extremely difficult. I agree that more work must be done in order to delineate this boundary more carefully, as I mentioned at the end of my article.

As you say, not all cases of hate speech can be considered dangerous speech, as I mentioned in relation to the Westboro Baptist Church. I find Susan Benesch’s framework on dangerous speech to be the most useful for determining whether or not speech can be considered dangerous. The case of the sports game between the Fighting Irish and Notre Dame is an interesting one, but as you say, very different from the Rwandan genocide or the post-election violence in Kenya. I would argue, as you do, that this case would not be considered ‚dangerous speech‘ using Benesch’s definition. She uses many variables to determine whether speech is dangerous or not. As listed in the article, these include: the level of a speaker’s influence, the grievances or fears of the audience, whether or not the speech act is understood as a call to violence, the social and historical context, and the way in which the speech is disseminated. Thus, context is very important, as you suggest, and this is something taken into consideration in Benesch’s framework and in the cases of Rwanda and Kenya. The fans in the sporting game would thus not be considered criminal using Benesch’s framework.

Ultimately, as you suggest, it is imperative that the line between hate speech and dangerous speech is more carefully drawn. It is crucial to keep on having these debates in order to further our understanding.

I also recommend that you read the case study on the Westboro Baptist Church available on this website, as it may provoke more critical discussion and debate: http://freespeechdebate.com/en/case/westboro-baptist-church-the-right-to-free-speech/

reply report Report comment

This is an interesting piece. My question would be: You mentioned the Kass FM rhetoric was in response to a perceived rigged election where most Kalenjin identified with candidate Raila Odinga. Do you think the way in which Odinga encouraged protests against the election count as inciting hatred? We can understand why Ruto and Kenyatta were indicted on suspicion of directly organising violence, but if Arap Sang is on trial for stirring things up vocally, surely Odinga fits the same category?

reply report Report comment

The first problems occurred in this situation we must confirm is that hate speech definitely not a type of free speech. There is no doubt that the boundary of freedom owned by a person couldn’t hinder the freedom of other people.

That means: Everyone has right to express himself, and should protect other right equally. To hurt others can not get free, but detain own soul.