In the landmark case of New York Times v Sullivan, in 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that criticism of public officials must be protected, even if some of the claims were inaccurate. Jeff Howard explains.

The case

On March 29, 1960, a fundraising appeal appeared in the New York Times on behalf of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and his fellow civil rights activists. The letter described various altercations that King and his colleagues had with police in Montgomery, Alabama. Several of the details that appeared in the description, however, were false. While the letter indicated that King had been arrested seven times by police, he had actually only been arrested four times. The letter also asserted that Montgomery police responded to a student-run sing-along of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” by surrounding the peaceful protestors “with truckloads of police armed with shotguns and tear-gas”. Other protesting students, the letter insisted, were cornered in their university dining hall, the door “padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission.” Neither assertion was true.

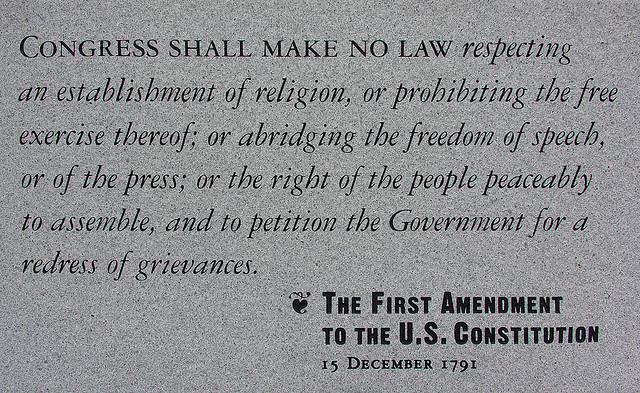

L. B. Sullivan, the Montgomery public safety commissioner, argued that the advertisement was an instance of illegal “libel” – published falsehoods about a person that harm his or her reputation. While Sullivan’s name was not mentioned in the New York Times appeal, he argued that his status as leader of the Montgomery police meant the letter was, by implication, defaming him. While an Alabama court awarded Sullivan $500,000, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed the decision on 9 March, 1964, arguing that Sullivan’s status as a public official triggered a higher standard of proof than were he a private citizen. Public policy debate must be allowed to be “uninhibited, robust and wide-open”. Specifically, the Court argued that anyone found guilty of committing libel or defamation of a public official must be guilty of “actual malice” – of knowingly choosing to lie and do harm – and King’s supporters were not. The decision fortified the freedom of the press in the U.S., making it extremely difficult for government officials to punish citizens for making even false claims about them.