How do we strike the right balance between freedom of expression and child protection? Sarah Glatte explores a proposal by the British government.

The case

In July 2013, British prime minister David Cameron sparked a media debate by announcing plans to “crack down” on online pornography. Arguing that the internet had created a “cultural challenge” for child protection, Cameron declared that an agreement with four major British broadband providers had been reached to introduce automatic online filters to block pornographic content on private networks. According to the proposed measures, family-friendly filters would be enabled by default on all newly purchased British broadband accounts, and existing customers would be contacted by their internet providers to choose whether or not to install them. The prime minister stressed that it would be possible to disable network filters, but that this could only be done by the adult network account holder. In addition, Mr Cameron announced that videos streamed in Britain would become subject to the same restrictions as video material sold in British sex shops.

The new regulations were met with widespread criticism. Opponents of Cameron’s proposals expressed fears that such measures could jeopardise “longstanding efforts to prevent or abolish censorship … and protect civil liberties and human rights worldwide.” “What began as a crusade against child pornography,” one commentator remarked, turned into censorship of legal adult content. Critics also voiced practical concerns that porn filters might not be able to distinguish between pornographic and educational material, and that they could in fact be too easily circumvented.

reply report Report comment

There is no need for pornography to be in any way limited. Because it is not dangerous even for kids.

reply report Report comment

Hi everyone, I feel the need to make this short comment. First I think we should perceive this issue, at least too some degree as part of a comprehensive package of obtrusiveness into our lives by various state actors, and foreign powers. This sort of politics is rife throughout the land, local and national. Deals or mutually advantageous situations for both government and the gutter press will be nurtured along. Peer pressure will play a vital role in gaining support for this policy, along with trendy ‘sound bites’. I believe there may be a wave of hysteria, whipping the public into a frenzy. No one really seems to have made a clear definition of what pornography actually is, where does one measure from. From a little research I’ve done there seems to be great diversity of opinion. Governments doing good things for the public and strongly supported by the cheap newspapers are the way things are done now; but most are done for far from good reasons; rather to serve surreptitious agendas. Yes we must protect children; but I fear the government wants to use them as hostages to force their plans to come to fruition.

reply report Report comment

Hi. I don’t think it is possible to apply the same sort of rules to online life as offline and if it was then it certainly would rob the internet of everything that makes it special.

One example of this is the British Government’s attempts to stop banks paying credit card payments from UK customers for using porn sites which do not have proper age verification. This can in theory be done for sites within the UK and sites in non-UE foreign countries. However, it cannot be done for sites based in EU countries as this would contravene EU law. Within the EU, the lwas that apply to websites are those of the host country. However, the UK Govt wants to treat foreign websites as though they were broadcasting in to the UK. There has even been talk by some overzealous people of saying we should try to extradite owners of foreign websites which don’t have age verification because they are potentially broadcasting unsuitable material to UK minors. This is a very unusual conceptualization of the internet. There is no way that the US Government would extradite website owners to the Uk for something that would not be an offence in the US, especially when the UK is powerless to take a similar action against website owners in the EU. It should be remembered that there are many things on UK websites such as advice for gay people which would be considered inappropoirate in a number of countries where homosexuality is illegal. We could never have a situation where all the material on the internet was suitable for every other country.

Yet David Cameron does seem to want to tame the internet. ATVOD, part of OFCOM wants to regulate any type of video service which could in any way resemble a tv channel. The Cameron Government wants to claim cyberspace as an area for Government regulation. There is support for this from the conservative Daily Mail but also from feminist writers oin the Guardian and New Statesman. In some ways this is ironic considering how much the Guardian has campaigned to stop Governments snooping on citizens.

The consequence of Governments trying to control the internet in different territories would be to balkanise the internet and take away the international dimension of it. It is not possible to introduce systems of ratings or licensing without introducing a system of charges, barriers, licensing fees and accompanying bureaucracy. Lets say you are a blogger in Iraq who puts up weekly podcasts about your life in that country. You are not going to pay fees to the UK authorities and/or any countries who demand such fees or licensing. You would not understand all the internet laws of different countries and even if you did you would not be able to afford them. The only way that UK citizens would be able to access such material in a balkanised internet wouod be for large publishers to package such material and then charge UK subscribers for bundles of material. However, they could refuse to carry certain types of material and in any case it would take away the best thing about the internet at present which is that it is virtually free to publish on it and very easy to receive material once it is published. The only people who will profit from a a balkanised internet is large media companies who may get a chance to regain control of media and Governments who want to restrict what people can access.

The feminist groups who are campaigning against easy access to pornography on the internet could potentially cause serious damage to internet without achieving any of their goals. Similar to alcohol, tobacco and soft drugs such as cannabis- the demand for pornography is to high and the profits too high – to make prohibition (or even control) effective or viable. Within a few days of David Cameron announcing internet filters, free software for bypassing them was being advertised online. There is also the danger that any attempts at a wider or more stringent filtering policy will encourage more people to get a VPN which will give them access to the dark internet where a lot of illegal activity occurs.

There are wider attitudinal and political issues surrounding the internet – but that is for another discussion.

I have an academic article coming out soon as book chapter kin this subject. Please get in touch if you are interesting in further discussion or collaboration. j.greer@tees.ac.uk

reply report Report comment

Thank you both for your comments! You both make very valid points. With regards to the claim that pornography has become more violent – I am very happy to stand corrected on this as I did not scientifically investigate this statement myself. Due to the lack of quantitative research on the changes over time of pornographic content, it seems both points of view currently rely mainly on anecdotal evidence.

I feel it may be useful to reiterate, however, that this was not intended to be a debate about banning pornography in general – which I would consider a very problematic approach. I also intentionally did not cite any research on the negative effects of pornography consumption among adults as I know this is a fiercely contested topic. The question I was interested in (and on which I would love to hear your thoughts) is whether the rules which regulate our lives offline (such as age restrictions on pornographic material) should also be applied online and if so, how this could be done without undermining the fantastic medium that the internet has become.

reply report Report comment

There is some discussion of Prof Dines book here (behind a paywall, I’m afraid).

http://vaw.sagepub.com/content/17/5/666

At a recent conference on these issues I argued that what one would *expect* to see in social scientific literature where a deplored behaviour has little causal effect on undesirable outcomes is (a) a cacophony of results (b) very few replications of positive results (c) the few positive results found are, though statistically significant–ie probably not random–small in effect and explain but little of the variance (d) are mostly confined to experimental settings with little long-range follow up (e) are over-selected for in publication decisions (editors are less keen on publishing papers that conclude ‘nothing happened’, or ‘we can’t tell’, and (f) massively over cited and then re-cited in the secondary literature.

When I pointed this out, an intelligent and thoughtful participant nonetheless said, roughly , ‘but absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.’ This shows a profound misunderstanding of the nature of evidence. When thousands are looking and few are freakishly finding this *is* evidence of absence. The existing results are precisely what one would expect to see if the availability of pornography were a fairly insignificant vector in causing rape, sexism, discrimination, and the brutalisation of society.

In contrast, the social consequences of jailing people for three years for the mere possession of ‘extreme pornoraphy’ are malign and well established.

reply report Report comment

I would like to address the statement ( and it was a statement) which you made that pornography was belong more extreme and violent. The link which you include in support of this to a BBC article quotes two main sources. One is the head of ATVOD. This is an organisation which had no real purpose a few years ago. It was set up as an offshoot from OFCOM to answer public complaints about the online offering of tv providers. It has since tried to expand its remit through legal challenges to ‘broadcasters’ to becoming a body which can ‘regulate’ potentially anyone that puts up a podcast on their Internet site. ATVOD has also adopted pornograohy as a hobbyhorse to help justify its existence. It’s Director is moral entrepreneur.

The other main source is Gail Dines. Despite being a Professor of Sociology, Prof Dines mainly writes in the Guardian and populist books like her Pornland. She is not a dispassionate academic bit rather an anti-porn campaigner who has stated that her goal is to close down the porn industry.

I am writing an academic book chapter on a related subject at present.

reply report Report comment

Dear Leslie,

Thank you so much for your comments! Please let me try to address some of the issues you raised.

1. You are correct in saying that there is no scientifically robust research to back up the claim that pornography has become more violent and abusive. I cite Peter Johnson here, formerly head of policy at the British Board of Film Classification (the link to the original BBC article is imbedded). I think it is worth reflecting on a point made by Gail Dines in her book Pornland. She argues that we should not assume that online pornography is simply demand driven and that pornography producers only provide the material that viewers want to watch. Like many businesses, the porn industry is trying to create demand, to shape customer preferences and so on. The argument is that competition in the industry as well as consumer desensitisation have pushed porn toward hard core extremes. Like any other business, the porn industry should be scrutinised with view to its effects on consumers. I think this scrutiny is currently non-existent.

2. Your second point of forcing consumers to opt out/in as a way of naming and shaming is only an assumption, albeit one which should be considered carefully. In the first place, the proposal to introduce porn filters aims at making it more difficult for under-age internet users to access pornographic content, which is not deemed suitable for their age. In theory, ‘opting-in’ to be able to access online pornography is comparable to being asked for your ID when purchasing any product (be it pornography, alcohol, other legal drugs, or weapons) in high street shops. I agree, however, that in practice, the current proposal of how to opt in or out of these porn filters is problematic and that better solutions must be found.

The other issue which you mention is whether or not the government or internet providers are – or should be allowed to – retain records of those who opt in to access pornography. I agree that this would be highly problematic and detrimental to the protection of citizens’ privacy rights. It would be important to have legislation in place to assure that those records are not being kept or made accessible in future. The underlying question for me was whether the same pornography regulations should apply online as offline.

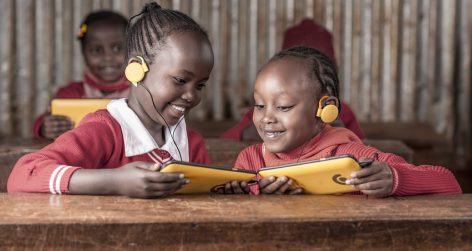

3. I think it is easy to forget that many governments already restrict what their citizens can view online – often of course to the detriment of free speech. For example, if I am not mistaken, Western governments already put a great amount of effort into monitoring the activities on religious fundamentalist websites. But I believe your point also misses the intention of the proposed policy legislation. The aim is not to ban pornography outright, but to make it inaccessible to children for whom this content is deemed unsuitable. Again, offline, we already have age restrictions for viewing, reading, or consuming pornography or violent content that is considered harmful to minors. The issue for me is not whether we should ban material for all internet users (this I would equally reject), but if and how we should enforce ‘offline rules’ online.

reply report Report comment

I have three reservations about Sarah’s thoughtful comments:

1. I’m not sure if I count as an ‘expert’ but, as far as I know, there is no valid and reliable empirical evidence that shows that: “mainstream online pornography has become both physically and verbally more extreme, violent, and abusive.” More than what baseline? Remember that there has been a massive change in the *selection* effect: now lots of people can *see* what lots of other people find sexually interesting, and it horrifies them. In 1983, most people had no idea at all what most other people actually viewed, let alone what they would have viewed if they could. A valid measure of the sort Sarah needs must give a plausible and consistent index for ‘extreme’ and ‘violent’. We do not have have one. A reliable measure must get the same result when applied in different contexts, by different researchers. We do not have that either. (Indeed, most of the empirical studies about the *character* of online pornography have not had even one replication.) We just do not know whether the pornography actually consumed by people online is, now, worse, or better, or just different than it was pre-internet. (We do know that *more* is consumed. This is not surprising: when the price of a normal good falls, more of it tends to be consumed.)

2. Over-blocking is not the only relevant issue. What do we think about the motivation for, and likely effects of, the requirement that families (adult men, typically) will need *expressly to ask* for access to pornography? I think that part of the motivation for that policy is to *shame* men who use pornography, to *humiliate* them in front of their families, to *expose* them to the likelihood that the ‘smut list’ that will be retained by each ISP will eventually become public–all in order to frighten them from viewing any pornographic material at all, even in the privacy of their homes, even when it is perfectly lawful. I think it is wrong for governments to act with the motivation of shaming, humiliating, and frightening men in this way.

3. Would we be willing to endorse similar opt-in requirements for access to other online material where there is at least as good evidence that use of that material tends to produce behavioural changes that many regard as malign? Plausibly, viewing material from various fundamentalist religions tends to make its viewers: less tolerant of others, more sexist, more homophobic, and in some case also more violent. (Indeed, mainstream religions–not just fundamentalist ones–are among the *most* reliable vectors of sexist socialisation in the modern world. Strong religious conviction is positively correlated with just about all traits that feminists and liberals deplore. ) Would we endorse an opt-in scheme to protect people from unwilling, or easy, exposure to religious materials online? I would not. Against the speculative social benefits we need to set religious freedom. Everyone sees that. The case of pornography is similar.

***

Plug:

I explore some of the issues about online obscenity in:

‘Obscenity Without Borders,’ in Rethinking Criminal Law Theory (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2012), 75-93.

And this article also takes up other key issues:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9760.00091/abstract