Scott A Hale apresenta alguns dos efeitos quando se busca ou dissemina informações em diferentes línguas na internet.

A proposta de princípio 1 do Liberdade de Expressão em Debate aborda o direito “expressar, receber e buscar informações e ideias, independentemente de fronteiras.” Uma das fronteiras mais óbvias, mas a menos estudada é a língua. O LED reconhece essa questão e se engaja num impressionante programa de traduções de conteúdos para treze línguas.

Mas qual é o efeito real da língua na busca por e disseminação de informações na internet? As pesquisas atuais não costumam discutir essa questão fundamental, e obviamente não podemos tratar disso de forma aprofundada aqui nesse curto texto. Contudo, páginas de buscas mostram diferenças de conteúdo dependendo de cada língua. Quando se busca por imagens, os buscadores tentam combinar as palavras de consulta com o texto que aparece perto de imagens em páginas da internet, bem como os nomes dos arquivos de imagens e as palavras que aparecem nas ligações para as imagens. Por outro lado, seria razoável crer que os resultados da busca por imagens sejam similares em todas as línguas, já que as imagens podem frequentemente ser compreendidas independentemente de seus textos descritivos. No entanto, as imagens são carregadas e descritas usando configurações específicas de acordo com o contexto linguístico-cultural. Ainda que o Google não seja o buscador predominante em todos os mercados (Yahoo! no Japão, Yandex e Baidu têm mais fatias do mercado no Japão, Rússia e China respectivamente), esse é o buscador líder mundial, aplicando índices em imensas quantidades de conteúdo. Nesse sentido, seria possível presumir que o Google usa algorítimos similares, ou um único algorítimo, para buscar informações em diferentes línguas. Mas não é isso que acontece, e é por isso que as diferenças de resultados usando o mesmo buscador em diferentes línguas é algo que impressiona.

As figuras 1 e 2 mostram resultados de imagens quando se busca “Praça da Paz Celestial” em inglês e em chinês usando o Google. As buscas foram feitas consecutivamente através de um mesmo computador no Reino Unido pelo endereço google.com; os resultados são surprendemente diferentes tanto em situações banais quanto em questões mais sérias. Os resultados para “Praça da Paz Celestial, por exemplo, revelam uma disparidade no número de páginas catalogadas em inglês e em chinês sobre os protestos de 1989.

Estudos mais sistemáticos sobre as diferenças entre as edições em diferentes línguas da enciclopédia eletrônica Wikipedia também mostram “uma pequena e surpreendente quantidade de conteúdos que se sobrepõem nas várias versões da Wikipédia” (Hecht & Gergle, 2010). Em particular, é interessante que até mesmo a edição em inglês, que é de longe a maior, contém uma média de apenas 60% de conceitos que são discutidos em outras línguas analisadas no estudo (a maior sobreposição ocorre entre inglês e hebreu, com 75%). Na verdade, a edição em inglês tem apenas metade dos verbetes que aparecem na segunda maior edição, em alemão. A edição alemã, por sua vez, contém apenas 16% dos verbetes presentes na edição em inglês. Além disso, é claro que ainda que “duas edições em línguas diferentes podem conter claramente o mesmo verbete/conceito, as edições talvez descrevam o conceito de maneira diferente”, um ponto analisado por Hecht & Gergle (2010). Esses autores também discutem as novas ferramentas como a Omnipedia, que permite a usuários explorarem as diferenças entre as edições em diferentes línguas.

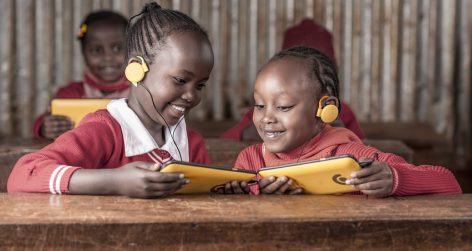

Mas isso não é um cenário desanimador. Muitas plataformas já atingiram reais penetrações globais (Facebook, Twitter, You Tube e Wikipedia) e ainda que as comunicações feitas nessas plataformas sejam linguísticas, estas plataformas também abrem a possibilidade de disseminação de informação através de fronteiras a uma velocidade sem precedentes. Minhas pesquisas sobre blogs que discutiram o terremoto no Haiti em 2010 (Figura 3) e sobre as partilhas de ligações da Wikipedia e do Twitter após a tsunami e o terremoto no Japão em 2011, assim como pesquisas de Irene Eleta sobre o Twitter, mostram exemplos de informações que são disseminadas através de diferentes línguas e onde usuários que se comunicam com vários grupos linguísticos atuam como pontes, permitindo que a informação flua entre grupos línguísticos diferentes.

A fluidez de informação entre diferentes línguas tem dimensões técnicas e sociais. Traduções automáticas contém vários erros, mas ainda assim permitem que conteúdos de nível elevado de diferentes línguas estejam em contato. Além disso, novas pesquisas e novas fontes de dados de treinamento vão ajudar a melhorar continuamente os sistemas de tradução automática. É certo que pesquisas sobre o papel do design no caminho para usuários descobrirem e difundirem informações em várias línguas, como a minha pesquisa, são necessárias, e empresas de mídias sociais deveriam usar estas descobertas e as ciências sociais em geral quando constrõem suas plataformas. Para concluir, é preciso mencionar as novas e interessantes ferramentas que vão alavancar as habilidades tanto de computadores quanto de usuários no sentido de cruzar fronteiras linguísticas. Doulingo e Monotrans2 são dois exemplos de ferramenta que permitem ao usuário monolinguístico traduzir conteúdos; no caso de Doulingo, é possível também aprender uma nova língua ao mesmo tempo. É claro que haverá sempre um lugar para a tradução humana e para asempresas de mídia que identificam e verificam informações sobre importantes eventos narrados em outrs línguas.

Scott A Hale é pesquisador assistente e doutorando do Oxford Internet Institute.

reply report Report comment

Dear Mr. Hale. My name is Victor. T.W. Gustavsson and I go the University of the Hague studying the meaning and use of the English language. After reading your article, I was left with some unanswered question marks. Do computers really translate information in a way that alters the content and meaning of a text from one language to another? And if so, should we leave these translations to computers, if it comes to the point where these faulty translation can cause harm and/or misunderstandings?

Your argument that different countries include different information about the same event is just logical, as different countries have dissimilar cultures and beliefs which will shape what information they focus on and the way they structure their information and websites. For example, Google searches in one language will not give you the same suggestions as if you would Google the same thing in a different language. So it rather comes down to internet censorship which plays a huge role when it comes to what information is allowed to be published on the internet, making these searches bias depending on what country you are searching from or in what language you make the search.

Furthermore, your images showing the different search results of China’s Google and the UK’s Google demonstrate the censorship of China compared to the UK’s freedom of speech. Your argument is based upon the supporting evidence that the search results are different, yet your example actually only proves the opposite as it demonstrates how much influence governments have on the internet. It is only logical that the search results in China will be different than in the UK due to their different cultures and standpoints regarding freedom of speech. If we look at the past, the UK has been much more open as a society and as a government compared to China, therefore, it would only be logical if this were to be represented on the internet.

You are simply stating the obvious. Instead of developing your own ideas or theories, you rephrase what has been addressed in the past by experts in the field. China’s government censors the internet, as the Tiananmen Square example shows; it has done so for years.You mention that “search engines provide one window into the differences in content between languages,” yet I have conducted my own research and have found that searching ‘911’ or ‘Taliban’ on the Arabic Google and the UK Google have similar findings, unlike the Tiananmen Square example. This search was carried out from a computer in The Netherlands, with only a few minutes time difference between each search. I believe your argument is more supporting of government censorship on the internet rather than false translation due to internet translations.

In countries where no government censorship is present, such as Afghanistan or the United Kingdom, the search results are similar because it represents what people post or search on the internet. This suggests that your argument that “search engines try to match query words to the text that appears near images in web pages” is invalid, as it is only due to government censorship.

It therefore should also not be striking that there are differences in results between different countries such as China and the UK, as you suggested. Yet Google, who are determined to encrypt their algorithms due to the recent NSA affair, will prevent China from censoring Google in the future as easily (Washington Post, “Google is encrypting search globally. That’s bad for for the NSA and China’s censor’s”). I am convinced that if we were to compare the results of a Google Images search of “Tiananmen Square” between the Chinese Google and the United Kingdom Google in five year’s time, there would be little difference, as technology is ever improving and censorship is becoming more evident. Therefore I am not sure what your argument states, as your resource contradicts your sophism, actually illustrating that the internet is not free, and that Google’s algorithms can easily be hacked by governments.

You stated that translations on huge encyclopedias such as Wikipedia, are generated by sophisticated computer algorithms which are not nearly as accurate as real-life translators. However, according to Bill Bryson’s Mother Tongue, different languages may have as many as thousands of different words for what we have in English only a few for, “the Arabs are said (a little unbelievably, perhaps) to have 6,000 words for camels and camel equipment”. This could possibly confuse these computer softwares to misinterpret some words which could eventually lead to “overlap” as you said. This raises a question of, just as it is people’s job to translate in real life, should there be designated translators whose job it is to accurately translate content from English to or from any other language. Before the internet existed, works were already being translated and these seem to be much more accurate than many of the articles and pieces on the internet. You can argue that these have been checked over and over again by publishers, but, do computers not double check?

You mentioned explicitly that there are large overlaps between English and other languages with “overlap is between English and Hebrew is 75%”, yet a few sentences later you stated that “several platforms have achieved truly global penetration (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Wikipedia)”. Nonetheless, one big reason why German contains about 16% of the articles in English” is because Wikipedia has a policy where users request pages to be translated. Because English is one of the primary languages in our modern world and most internet websites and activity is done in English, it is only logical to give the English language priority when it comes to translation. Therefore, only the most important (which the user thus decides) gets translated to a foreign language. Country specific topics such as the German National anthem should undoubtedly be different than when it is translated in English.

I do agree howbeit, that machine translations aren’t flawless and that in time these will get more and more sophisticated. But do we really want computers to take over almost everything in the digital world, even the one thing we have developed over the course of thousands of years as a human race, language?

reply report Report comment

Dear Victor,

Thank you for reading and responding to my article. I’m afraid, however, that there have been some misunderstandings. I respond to some questions and point out some of these misunderstandings below.

> Do computers really translate information in a way that alters the content and meaning…

I only mention that machine translation has some errors, and do not discuss machine translation in depth in this piece. The focus of this article is on the content produced by humans in different languages (of which human translations are a small part). In the case of human produced content, yes, there are often differences in meaning and content across languages.

> Your argument that different countries …

This article only discusses languages and not countries. The example Google searches are both performed in the UK on the .com version of Google as stated in the article. Only the languages of the search queries were different. I admit, however, that the example queries could have been better chosen (and originally I had a gallery of many examples, but for technical limitations of this site it was not included. It is available on my own website: http://www.scotthale.net/blog/?p=275).

> “search engines provide one window into the differences in content between languages”

I stand by this, and note that similarity between two languages for one search doesn’t disprove that there are differences between some languages (and data shows most languages). It is also important to note that Google is constantly changing its search algorithms, and it is very possible that they are now using translations of search terms to produce more similar image results in different languages. I know that this was already being considered two years ago when I wrote this article, but I don’t know if it has been implemented.

> In countries where no government censorship is present….

Again, I’m concerned about language, not countries, and

> I am convinced that if we were to compare the results of a Google Images search of “Tiananmen Square” between the Chinese Google and the United Kingdom Google in five year’s time, there would be little difference

I’m not sure on this point. Note again that both of my searches were from the UK and performed on the .com version of Google. If the Chinese government remains successful in ensuring that most mentions of Tiananmen Square in Chinese occur around benign photos (e.g., through controlling the publishing of content in the country with the largest Chinese-speaking population in the world), then any language-independent image search algorithm will most likely find these benign photos and rank them more highly than ‘obscure’ photos that occur around the phrase “Tiananmen Square” in Chinese in a small amount of content.

> You stated that translations on huge encyclopedias such as Wikipedia, are generated by sophisticated computer algorithms which are not nearly as accurate as real-life translators.

I do not state this. In general, Wikipedia does not include raw/pure machine translation without a human in the loop. (https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Machine_translation)

> You mentioned explicitly that there are large overlaps between English and other languages with “overlap is between English and Hebrew is 75%”, yet a few sentences later you stated that “several platforms have achieved truly global penetration (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Wikipedia)”.

There is no contradiction between these two sentences. The first discusses content overlap between languages; the second discusses the geographic breadth of users of websites.

> I do agree howbeit, that machine translations aren’t flawless and that in time these will get more and more sophisticated. But do we really want computers to take over almost everything in the digital world, even the one thing we have developed over the course of thousands of years as a human race, language?

On this point we can agree :-). Humans play important roles in producing, seeking, and consuming content in different languages. My research argues that a better understanding these human roles (particularly those of bilinguals) is needed in order to better design platforms. I encourage you to take a look at my own website and get in contact with the contact form there if you want to discuss anything further. http://www.scotthale.net/

Best wishes,

Scott