While China’s human flesh search engines can help reveal government corruption they can also be used to humiliate ordinary citizens, writes Judith Bruhn.

Human flesh search engines, a literal translation from the Chinese, are internet searches by people for people. In online forums or bulletin boards, netizens search for and share information to identify an individual, their whereabouts, personal and contact details. Most cases are people looking for lost relatives or friends. For example “Brother Sharp”, a confused homeless man, was reunited with his family after people posted pictures of him online.

However, the most famous cases are those of enraged netizens seeking out people of objectionable morality who they perceive as deserving censure. One of the best known examples is a video that emerged in 2006 of a woman kicking a kitten to death in her stilettos while a friend filmed her. Chinese netizens were disgusted and started to search for her online. Within six days she was identified as the pharmacist Wang Yu from Heilongjiang province. The cameraman was likewise identified as Li Yongjun, employed by a local TV station. Local authorities announced an investigation into the case but since China does not have animal welfare laws they were not charged. Li Yonjun, however, apologised publically. Both Wang Yu and Li Yongjun lost their jobs as a result of the human flesh search.

Human flesh searches can serve to aid the detection of corruption and social injustice. The case of Zhou Jiugeng, former director of the Property Bureau in the Jiangning district of Nanjing, is a prime example of this. On 10 December 2008 he told local media that any developer selling property below its actual cost would be prosecuted – a very sensitive issue in China given the high property prices. A day later a post entitled “Eight Questions to Property Bureau Chief Zhou” appeared, and triggered a wave of human flesh searches for Zhou. Netizens discovered a photo of him with an expensive brand of cigarettes costing £15 per pack. Several other posts followed, showing Zhou wearing a Vacheron-Constantin watch worth about £10,000 and driving a Cadillac. Given the modest wages of state officials, accusations of corruption followed. On 29 December 2008 he was dismissed from office and in February 2009 a formal investigation for bribery and gross violation of party discipline began. In October 2009, he was sentenced to 11 years for taking more than RMB 1 million (over £100,00) in bribes.

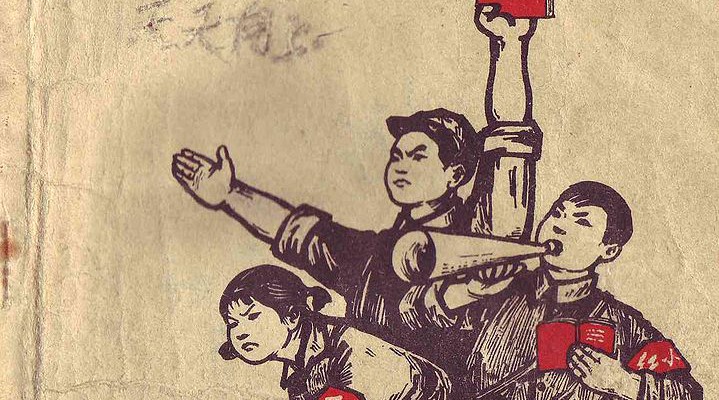

Chinese human flesh search engines are examples of netizen vigilantism. Even though this sometimes turns against party officials, the Chinese Communist Party seems to encourage this behaviour as it helps to weed out specific cases of corruption. As Rebecca MacKinnon points out, there is a strong tradition in China of setting the masses on local officials to fight corruption. In the Mao era this was very common practice. The New York Times even refers to human flesh searches as “Red Guards 2.0“. During the Cultural Revolution the Red Guards, young Chinese, rose up to “turn China red”, destroy the old and bourgeois elements in society. They often turned on their neighbours, teachers and even family in a brutal campaign against “bad class elements”. This is an interesting, if not entirely appropriate, comparison, drawing parallels between the Cultural Revolution’s struggle against people out of a complex variety of reasons and today’s online-initiated search for individuals, which has real-life consequences.

There is, however, a clear difference between the Red Guards and human flesh search engines; the former often knew the individuals they accused, violently attacked and sometimes killed them; the latter are usually searching for offending but personally unknown individuals and then possibly take online action, using words rather than physical assault. Private netizens initiate these searches out of their personal conviction, while the Red Guard movement was politically motivated and strongly backed by the government and Mao Tsetung. Yet, there are certain similarities, such as the feeling of responsibility towards society, the wish to fight injustice and corruption, especially in the case of party officials. However, another similarity is the uncontrolled group-dynamic of this online rage, which can lead to harassment of individuals who might not deserve such treatment.

For example, after a separation from her husband, Jiang Yan committed suicide in December 2007. Jiang Hong, the sister of Jiang Yan, posted her sister’s diary online, revealing her husband’s affair and her consequent separation and depression. What followed was a public outcry and human flesh search for the ex-husband, Wang Fei, and his girlfriend. Both were identified within a day and bombarded with telephone calls. Someone even painted red characters on Wang Fei’s parents’ front door. The multinational advertising agency he and his girlfriend worked for, Saatchi & Saatchi, issued a statement reporting that they both had voluntarily resigned, but Wang’s lawyer says they were forced to resign and went into hiding. While Wang Fei’s behaviour may have been immoral and his wife’s suicide deeply regrettable, divorces are not uncommon. In this case, the human flesh search amounted to mass harassment.

Wang Qianyuan, a Chinese student studying at Duke University in the US, also experienced the wrath of human flesh searchers. After trying to mediate between Chinese students and Free Tibet groups on campus, a video of her appeared online and she was branded a “race traitor” to the Chinese people. Her personal details and family in China were exposed and harassed. Human flesh searches can thus inhibit free expression and harm individuals and their families. Whether the searched people deserved the treatment they received, which often had real consequences for them, is a judgement made by those searching alone – not by law or other regulations.

Used like this it can limit freedom of expression out of fear of retribution. After the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, Zhang Ya posted a video of herself online, complaining that her favourite TV shows were interrupted by the earthquake reportage. Netizens started a human flesh search and threatened her so that she was taken in by the police for protection due to the high number of death threads she received. While her video post may have been inappropriate and deeply offensive to many, the case illustrates the serious nature of the searches and their possible consequences.

There has been some debate in China about how to regulate human flesh searches. Online forums and bulletin boards are held responsible for the content posted so that victims of such searches are able to sue the hosts of the human flesh search engines. Wang Fei was the first to take such steps and in 2008 sued Daqi, Tianya and the blog provider of his dead wife’s blog. Apart from this right to sue for slander or defamation human flesh searches are not regulated. Yang Tao, a government prosecutor from Jiangxi province explained in Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post in 2008 that human flesh searches are a necessary avenue for ordinary citizens to seek justice.

Human flesh searches may turn out to be a two-edged sword for China. While they can empower citizens in the face of corrupt officials, they can also serve those who wish to limit the freedom of speech of those they disagree with. This is a complex phenomenon that sometimes empowers and sometimes restricts freedom of expression.

reply report Report comment

Clearly the Chinese government have weighed the risks / rewards. Its continued existence would suggest it has a more significant effect on their ability to control freedoms than it does to empower people.

This is an extension of China’s extremely clever social strategy. If left unofficial, the government cannot be held responsible. It is the same policy employed upon state hackers and other party supporting organisations that operate in the grey areas of international law.