We regularly highlight comments that have made an impression on us. Antoon de Baets left an insightful response to Josie Appleton’s discussion of memory laws in France.

I admire the work of Liberté pour l’Histoire and fully support its analysis and goals. According to Josie Appleton, however, Pierre Nora and Olivier Salvatori said the following:

Terms such as ‘genocide’ and ‘crimes against humanity’ are now part of the everyday business of political claims-making. ‘These terms were once very precise’, says Nora. ‘A crime against humanity was a legal term applied after the Second World War, which involved the legal duty to pursue and bring to justice the authors of the Holocaust until their deaths. Genocide meant the decision to destroy a part of a population for racist reasons’. Now events including civil wars and the slave trade can be described in these terms. In Nora’s view, ‘it is a judicial absurdity to say that an event such as the slave trade was a crime against humanity’. The authors of that crime are several centuries long gone, and their intention was not to destroy a population. The more that the word ‘genocide’ is used broadly for ideological reasons, the more it becomes ‘a word that historians try to avoid’.

In contrast to the remainder of the interview, this passage is full of confusion. A few clarifications, sentence by sentence.

** “These terms were once very precise.”

This is correct, but the terms are now more precise than in the past. For the first definitions of “crimes against humanity” and “war crimes,” see articles 6b and 6c of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal (IMT) at Nuremberg (1945); for the first definition of “genocide,” see article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948). For presently internationally accepted definitions, see International Criminal Court (ICC), Statute (1998), article 6 for genocide (which definition is identical to article 2 of the Genocide Convention), article 7 for crimes against humanity (which definition is a complete redrafting of IMT text), and article 8 for war crimes (which definition is based on 1949 Geneva Conventions and 1977 Additional Protocols). In general, the passage confuses genocide and crime against humanity: every genocide is a crime against humanity, but not every crime against humanity is a genocide.

** “A crime against humanity was a legal term applied after the Second World War, which involved the legal duty to pursue and bring to justice the authors of the Holocaust until their deaths.”

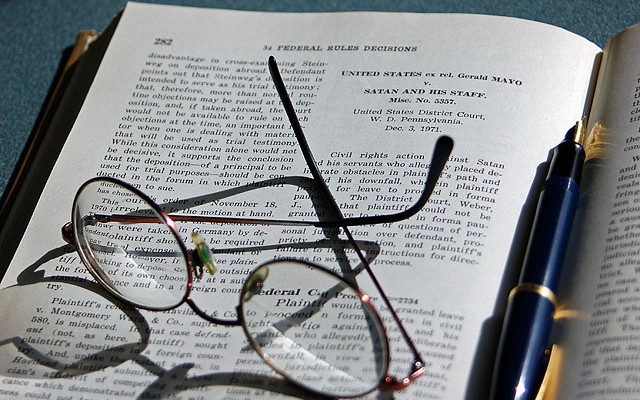

This is correct: the perpetrators of the Holocaust were tried for crimes against humanity and war crimes under the IMT Charter. But the Charter definition of crime against humanity is not “the legal duty to pursue and bring to justice the authors of the Holocaust until their deaths”; it is “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war; or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated.” At Nuremberg, the perpetrators of the Holocaust were not tried for genocide because the IMT Charter did not yet contain the genocide category. The United Nations General Assembly first affirmed that genocide was a crime under international law in Resolution 96 (I) (“The Crime of Genocide”) (11 December 1946). Genocide was a crime that only came into legal existence with the adoption of the Genocide Convention in 1948 and the latter’s entry into force in 1951. The Holocaust of 1939-1945 has officially been called a genocide since the adoption of the Genocide Convention. Nobody can protest in earnest against this case of retroactive labeling because the Genocide Convention was drafted precisely with the Nazi atrocities in the minds of the drafters. And many other crimes in history conform to the official genocide convention.

** “Genocide meant the decision to destroy a part of a population for racist reasons.”

This is not accurate: the genocide definition speaks of an intent to destroy in whole or in part; and the groups mentioned in the genocide definition do not only include racial groups, but also ethnic, national and religious groups.

** “Now events including civil wars and the slave trade can be described in these terms.”

(1) A civil war cannot be described as a genocide, a crime against humanity or a war crime. A civil war is the context in which such crimes may occur. In its 1977 Additional Protocols, the International Committee of the Red Cross was the first to distinguish the context of international war from the context of a “war not of an international character”. Such a distinction was urgently needed because by only covering gross crimes committed in international wars, a huge percentage of all gross crimes stayed in the dark. The distinction international / internal is also adopted by the ICC, but only for its definition of war crimes.

(2) For the slave trade, see my next point.

** “It is a judicial absurdity to say that an event such as the slave trade was a crime against humanity”.

This is not accurate: the slave trade is a crime against humanity but it is not a genocide. The ICC Statute determines that enslavement (a summary name for slavery and slave trade) was a subcategory of “crimes against humanity.” The Declaration of the 2001 World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance reiterated this view. Some define slavery inaccurately as a genocide or a “Black Holocaust,” but the slave traders’ intent was not to destroy the slaves but to exploit them as cheap labor. This was the view correctly held by Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau (and correctly rendered earlier in this interview, but not in the passage I discuss here).

** “The more that the word ‘genocide’ is used broadly for ideological reasons, the more it becomes ‘a word that historians try to avoid’.

It is correct that the word “genocide” is often abused (as in the example of the Black Holocaust above). Avoidance by historians of the term for that reason, however, is a weak offer. Some crimes are genocides, others are not. The use of recent concepts is not necessarily anachronistic and often plainly better than the use of concepts en vogue at the material time of the crime. (Space lacks to develop this important point here). We already saw above that retroactive labeling can be fully justified. In fact, historians do little else than retroactively labeling of historical events. To be sure, scholars and others retain the right not to adopt labels defined under international law for historical practices. They should, however, explain why their alternative label or definition is superior. I find such explanations, if they are given at all, seldom convincing. In cases of recent historical injustice, it is not recommended to define the nature of a given crime differently from international courts with their elevated standards of evidence and huge research departments. In cases of remote historical injustice, the use of either historical or recent concepts has to be painstakingly justified.

I elaborated these points at length in my “Historical Imprescriptibility,” Storia della Storiografia (September 2011) and “Conceptualising Historical Crimes,” Historein, no. 11 (2012).

Antoon De Baets

You can read the original post here.